I grew up with the oven on. In addition to baking meat and potato main dishes, my mother baked desserts: pies, cookies, quick breads dense with fruits and walnuts, and frosted cakes in every flavor, one each week. Also crisps and crumbles, caramel rolls, and coffee cakes.

Our kitchen, inexpertly designed by my parents, was the biggest room in our 1950s rambler house. Mom had a wall oven that she loved, even though it was located near the entrance to our living room, some distance from her cupboards and stove.

I grew up believing that my middle-class Falcon Heights neighborhood, where moms stayed home, cooking and baking, was the norm. It was a surprise then, when, in my twenties, I began to travel. A summer spent in Puerto Rico revealed an island seemingly devoid of baked desserts. Puertoriqueños instead enjoyed sweet guava paste, fruit cocktail, flans, and ice cream.

In 1980 as a newlywed, I visited India, my husband’s country. There I was served a popular dessert called (I am serious) barfi, which involved milk boiled down to its sticky essence and then cut into squares. Boiling milk, I discovered, was how many Indian sweets were made. I fell in love with paisam, a pasta-based pudding bursting with cashews and raisins. I ate ladhus, sweetened balls of boiled lentils, some sticky and others powdery, and jalabis, deep-fried sweets.

Clearly not all countries eat baked desserts. Why not? Because not all countries have an oven tradition.

The earliest ovens, pits of hot coal and ash, originated in Central Europe, Egypt and Greece. During the Middle Ages, Europeans used fireplaces not only for heating, but for baking. This practice spread to Russia and North America, but perhaps because of the heat fireplaces generated, it was not taken up in warmer places. Exceptions are often due to colonization; for example, Vietnamese people are skilled at French pastries. In non-fireplace parts of the world, cooking traditions centered around cooktops.

I lived in Turkey from 2010 to 2013, a place where baked desserts are a recent import. Turkish desserts center instead on stove-cooked puddings, and on baklava, created not by baking phyllo dough, but by drying thin sheets of it and then layering them with nuts and honey.

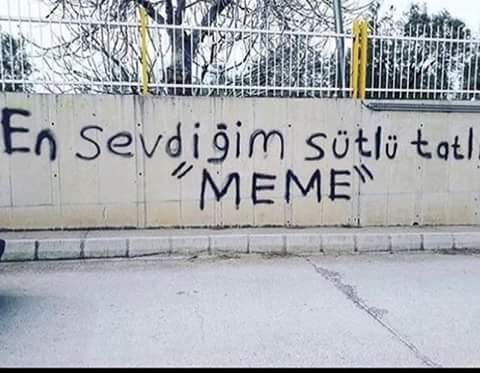

Puddings are so popular in Turkey that there are establishments devoted solely to “Sutlu Tatli,” milky desserts. In those, I ate sütlac, perhaps the most popular Turkish sweet, a non-pretentious rice pudding with a blackened top; kazandibi, rubbery, but tasty pan scrapings; and tavük göğsü, a pudding that contains threads of chicken breast. I never tired of seeing Turkish men, stocky and sometimes fierce-looking, spooning up soothing white creations.

Turks also make asure, Noah’s pudding, a gelatinous concoction of grains, fruits, dried fruits, and nuts each year to commemorate the landing of Noah’s Ark. They then distribute it to friends; I was touched one evening when a young neighbor woman I’d barely spoken to appeared at my door with a tray that held dishes of asure.

With globalization, the concept of baking desserts has spread like batter in a pan. On a recent trip to Mumbai, there was a bakery across from our hotel called The Brownie Point. In Turkey, I also found cookies and brownies, but they were sometimes dry or overly dense. Cheesecake was becoming popular there, however, and it was usually delicious. It occurred to me that, just as Turkey is a bridge country, cheesecake is kind of a bridge dessert, a compromise between milky pudding and standard cake.

I’ve never met a sweet I didn’t like, but have to confess a preference for baked desserts. Accustomed to apologizing for my culture’s rapaciousness and complacence, I realize that, in the dessert domain, I can brag. I am proud to have descended from long tradition of bakers. When I bite into a sweet roll or a piece of coffee cake, I feel solidarity with Northern Europe and my female ancestors of yore, pale stocky women with strong arms from mixing stiff batches of dough. But mostly I think of the trail of fragrance that accompanied my mother like a steamy flag as she carried her latest sweet creation across the kitchen.

To make Noah’s pudding, go to:

https://www.thespruce.com/turkish-noahs-ark-pudding-3274180

Hi Sue. I loved your articles and am enjoying the fourth one in a row. It’s fun to see our “so ordinary” things from a foreigner’s perspective. I couldn’t help but laugh when I saw the photo with the “meme” thing. It’s so cute. I’d like to tell you what the graffiti actually means, if you don’t mind. It says “Tits: my favourite milky dessert”. There’s no establishment called “meme” in Turkey. And I don’t think that there will ever be 😉.