Our children, Angela and Gregory, are here and we’ve been sightseeing. We visited Istanbul’s Grand Bazaar, Topkapi Palace and the Hagia Sophia, and drove up the Bosphorus to the Black Sea. On Sunday the 22nd we left town for a five-day trip to Turkey’s west coast, the most progressive and prosperous region of the country. We were headed toward the ancient Roman city of Ephesus. The Turks call it Efes, and have named their national beer brand likewise.

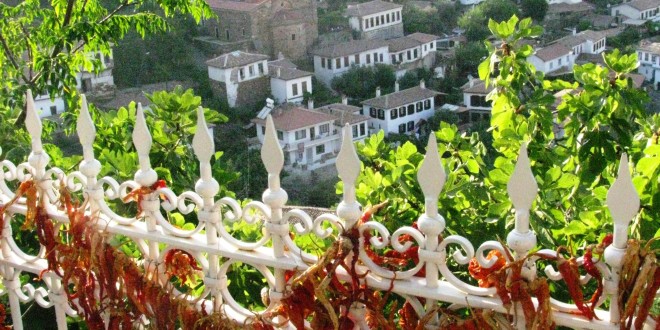

After a full morning walking and climbing around the ruins of Ephesus, in midafternoon we are back in the little village of Sirince (pronounced Shi RIN jay), above which sits the country cottage we’ve rented. Hungry, we choose from one of four mostly-empty outdoor restaurants on Sirince’s main drag, sandwiched in among shops selling white peasant dresses and colorful pottery.

We sit down at a table in a garden, and a man of perhaps 27 or 28 emerges from an out-building that is probably a kitchen, carrying menus. He is medium height and handsome, with sandy hair and green eyes, coloring not so unusual here. For a country with few immigrants, Turks are remarkably diverse.

“Where are you from?” he asks, and when Sankar tells him the U.S., he looks at me and says, “Yes, you look like an American.”

“You also look like an American,” I counter, only to see his face fall.

“I don’t look Turkish?” he asks with real concern in his voice. He is a grown man, but I apparently hold his identity in my hands.

“You also look Turkish,” I reassure him.

We order flat bread stuffed with eggplant; kofte, the national dish of spicy meatballs; and soup, a strange choice given the heat, but savory liquid sounds appealing. As we wait for our food, a group of teenagers comes in and sits down a few tables behind us. They look about 14 or 15-years-old, three girls and two boys. There are no adults with them, nobody brought them here; they are residents of Sirince.

The four of us chat and I am not facing the kids, but at some point Angela says, “Look, they are drinking!” And indeed several of the teens are sipping from glasses of rose wine. I wonder what kind of behavior we are going to witness.

Our lunch comes, along with several frosty bottles of water. In the summer heat I am often more eager for water than for food, but the food is delicious. While we dig in, the kids get up and move to another table. Now they are sitting in my line of vision. One of the boys has a smooth face that is almost pretty, and a lanky, not-yet-filled-out frame. His hair is also sandy in color. The kids are talking animatedly and one of them is feeding bread to the black and white restaurant cat.

“I have never seen kids this age drinking in a restaurant. And in a Muslim country during Ramadan,” I comment. The legal drinking age in Turkey is 18.

We launch into a conversation about the drinking age in the U.S. Angela feels it should be lowered, that kids’ first drinking experiences should be under family supervision, not away at college where they’re pressured to binge. I am skeptical; I saw a lot of bingeing during my own college days, when the drinking age was 18.

The waiter appears with a couple of fat goblets of beer for the teens. We realize that he must know them; perhaps he is related to them. The population of Sirince is only 800. We also realize that, while we find Sirince peaceful, these kids probably find it excruciatingly boring. We talk about other topics, but ever so often my eyes move to the kids, contemplating the situation.

Our waiter emerges from the kitchen and asks if everything is okay at our table. But then, “I don’t smoke, and I drink lots of milk,” he tells us, to our astonishment. “Every day I drink two glasses or more.” We nod at him and murmur approvingly. After he walks away, we chuckle, “thanks for sharing that,” and Greg murmurs, “T.M.I.”

“Maybe he saw us looking at those kids,” Angela says. And I realize that she is right. He was probably watching us from the kitchen window. Often we are given help here before we even ask for it; the Turks are attentive to strangers—really to anyone—in their midst. But that means that we are observed even when we aren’t in need.

As we finish our food and sit talking, the waiter carries some stuffed pita bread and kofte out to the kids. Then, a few minutes later he approaches our table with something we didn’t order. He sets it down in front of us, a plate of plump, rich-looking peach slices. “I want you to taste these. They are from my own tree,” he tells us.

“Tesekkular,” we exclaim, thank you. The fruit is tangy and surprisingly juicy. I wonder how fruit juice can come from soil that looks so barren. On our drive from Istanbul, we passed dozens of stands selling heavily-ripe melons grown in dry, thorny fields.

We thank him and I ask him if it is difficult to grow peaches. He tries to answer, but the topic is beyond his English repertoire. As he casts about for words, he holds his left arm out to the side, snapping his fingers as if he’s impatient with himself. He ends up telling us that no, it is not hard, but yes, it actually is hard.

A few minutes later, as he takes the money for our food, he stops for a moment. “I would like to see you again,” he tells us. “My name is Ali.” We thank him several times with wistful smiles. Then we walk past the kids, eating quietly, and out of the restaurant.

Just this week I went swimming with one of my biking friends, Gretchen, in Square Lake. When we got back to my house, we snacked on fresh Colorado peaches that a friend had trucked in that day.

“Wow!” Gretchen said, “The last time I had a peach this good, it was in Turkey. They have the most amazing peaches there.” Gretchen had been an AFS student in Turkey. When I told her I had a good friend living there for the next couple years, she told me I absolutely HAD to go. I am saving my pennies!