What can a trip to Morocco teach us about ourselves? I was surprised to find out.

I have been thinking of Morocco for decade, and came close to going to that country decades ago, when a prospective employer, Catholic Relief Services (CRS), invited me to New York. I was going to interview for two jobs, one in Morocco, and one in a country called North Yemen.

Enthused, before the interview, I sat down with a colleague at the Boston clinic where I worked. Her husband was Moroccan and we leafed through her family photos. I began to imagine working in this country, less than ten miles south of Spain.

Alas, when I arrived in New York, the people interviewing me talked only about Yemen. Perhaps they had filled the Morocco position. Perhaps it was a bait-and-switch move. I never asked. I took the Yemen job–a year and a half of harsh conditions but warm hospitality–and didn’t look back.

In 2015, I was invited to join a tour of Morocco with a friend who’d had a diplomatic posting there. Alas, my teaching duties prevented me from going.

Finally, in 2024, my husband and I found ourselves making plans, along with friends Joan and John, to visit Morocco.

Morocco is the size of California, both in population, about 38 million people, and in land area. It is an expansive country with over 1,500 miles of Atlantic and Mediterranean coastline, wheat-producing plains, and rugged mountains. Arabs call Morocco Maghrib, which means sunset.

The Alawi dynasty, that traces its lineage back to the prophet Mohammed, has governed Morocco for almost three hundred years. It was never an Ottoman colony but was a French—and also Spanish—protectorate from 1912 to 1956.

Before we started on the tourist circuit, we took advantage of a Yemen connection. My Arabic teacher from those long-ago days, a linguistically-talented American named Rod, had married a Moroccan woman and was staying in Casablanca, where we landed. Over a tasty dinner of lamb tagine seasoned with prunes, and seafood wrapped in phylo, Rod gave us an overview of the country.

He described a relatively benign king who has completed important infrastructure projects, some in anticipation of the 2030 World Cup, which Morocco will host with Spain and Portugal. He told us Moroccans are mild-mannered, and that the country has integrated its historically nomadic Berber people (the term now favored is Amazigh), officially recognizing the Berber language and teaching it in school.

We had time to stroll through Casablanca’s old city, passing olive sellers and stands offering crusty, disc-like loaves of bread. We saw oranges everywhere and realized we would be able to drink as much freshly-squeezed orange juice as we wanted in Morocco. For Sankar, that meant every meal!

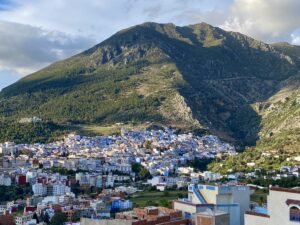

Jet lag, rain, and long hours on the road characterized our first days in Morocco. Chefchaouen, our first stop, is a small northern town nestled in the Rif mountains. Its houses and streets are tinted blue. Historians believe this colorization originated in the 15th century but it was reportedly enhanced in the 1930s by Jewish people fleeing the Nazis. We enjoyed wandering Chefchaouen’s impossibly confounding streets, but due to wet weather didn’t get to enjoy our large balcony or trek to a nearby waterfall.

We heard the haunting, melodic prayer call four times each day in Morocco, a wonderful link to my time in both Yemen and Turkey, but thankfully were not woken up by the additional call that comes at about 5 am. Mosques in Morocco have square minarets, different from the rounded ones I was used to in Yemen and Turkey. I grew to like how substantial they looked.

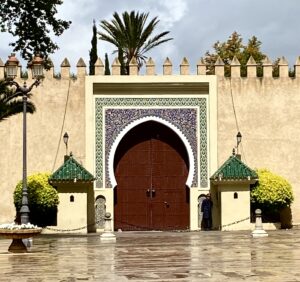

We visited the crenellated-walled Old City in Fez, as well as a leather tannery and a museum of wood carving. Fez has a reputation for crime, however, and its souks seemed full of shoddy imports. One young vendor followed Joan and me after we left his shop, stopping us a block away and begging her to “give me a price” on a small, machine-made tea pot she had looked at. We felt sad to see this desperation.

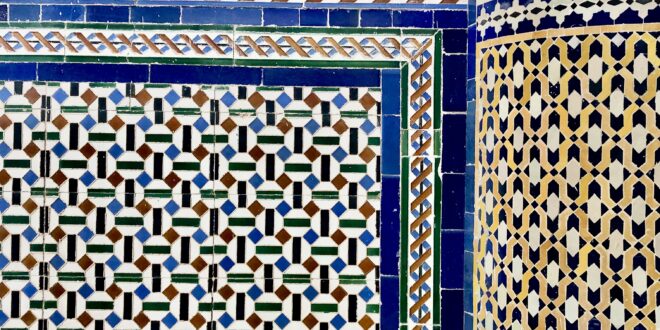

One of our stops that day, our guide informed us, would be to a ceramics factory. That sounded less than attractive, but the place turned out to be full of skilled artisans throwing clay pots and then etching and painting them with pretty designs. “You shouldn’t call this a factory,” I advised him. “Call it a workshop!”

Sunny, warmer weather boosted our moods in Marrakesh, just west of the High Atlas mountains. The city’s outskirts are modern, its buildings uniformly pale orange in color, and its thriving Old City is home to splendid palaces, ornately decorated old homes, and a madrasa that is 500 years old. Just outside the medina sit the luxuriant, walled Majorelle gardens with boldly colored buildings that blend both Art Deco and Moorish influences.

Our hotel, the Riad Kniza, was off one of the Old City’s main thoroughfares. Rose petals adorned its fountains and rooms, and we enjoyed tropical foliage and reflecting pools in its courtyards. Lavish rooftop breakfasts, cheerful, attentive (mostly female) staff and restful ambience placed Riad Kniza among the very best hotels we have ever visited.

It was great fun weaving our way through Marrakesh markets and ducking into darkened passageways that opened onto surprising vistas. We felt a sense of accomplishment that we had come far from home, but had nothing to fear.

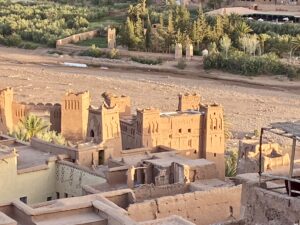

For our last few days, we drove south into the desert and stayed in an old, fortified village called Ait Ben Haddou. It is an excellent example of Moroccan earthen clay architecture and has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1987. This part of Morocco reminded me of Yemen.

Our hosts, the Tebi family, provided comfortable accommodations, albeit sans electricity. We knew this when we booked, and it was another link to my time in Yemen. Sankar, Joan, John, and I enjoyed climbing up and down the multi-level village, sitting on rustic decks to view the desert, and eating and reading by candlelight.

Along the way we were getting to know some young Moroccans: our driver for the entire ten days, as well as several tour guides, one in Fez and one at a movie studio in the desert town of Ourzazate, where films such as Gladiator and Lawrence of Arabia, and scenes from Game of Thrones, were created.

All of these men were accomplished linguists, speaking four languages: Arabic, Berber, French, and English—and sometimes also Spanish. It is worth noting that these languages encompass three different alphabets. None, however, had been able to get jobs better than driving or tour guiding.

Rashid, our guide for the day in Fez, was a small, intense man who wore a perfectly-pressed wool jalabiya, a floor length, thin, drapey overcoat with a hood. This is a very common garment in Morocco and is, to my eyes, flattering, as many Moroccan men are tall and thin.

Rashid seemed exquisitely knowledgeable about the area’s history, but as the day wore on, he increasingly led us to shops with “craft demonstrations” that seemed like tourist snares. When I murmured that our guidebook had warned us about textiles made of “cactus silk” (they are apparently often Chinese rayon), he became testy. After that, we decided to forgo the last few shops.

On one level I understood; he was almost certainly underpaid and was hoping for percentages on our purchases. And we probably seemed like immensely wealthy Americans. But it was a disappointing end to the day.

Another guide, whose name I can no longer recall, took us around the various movie sets that comprise Atlas Studios in Ourzazate. A tall, dark-skinned man of perhaps 35 with an impressive knowledge of films, he managed to convey to us in a tour that lasted just an hour and included thirty other attendees, that he had degrees in French law and in art, but he’d only been able to get work as a studio guide. That was a sad situation, and I did wonder if Moroccans discriminate against people who are darker skinned.

Our driver throughout the trip, Fadl, was a restless, good-looking man in his mid-thirties. He was happy to discuss life in Morocco. But his frequent comments, “I told you,” whenever we brought up a topic he had already touched on (perhaps, I thought, he was channeling authoritarian schoolteachers) made me hesitate to ask further questions. And his divulgences about his love life were, for me, TMI. I have generally found Arabs reticent about their personal lives, but have also met people who seem to think that, with Americans, anything goes.

Fadl told us that salaries in Morocco are low even for college graduates, with the exception of doctors and engineers. People in other professions, including teachers, he said, are poorly paid. He went on to state, “I don’t want to have children in this country.” His bitter words made me catch my breath.

It turns out Fadl had one foot out the door: a fiancee in the U.S. who was some years older, and his immigration documents being readied.

As an ESL teacher I often work with recent arrivals. But here was someone on the brink of leaving, a young man about to completely change his life.

As our van wound through the high Atlas Mountains, I thought about Atlantic crossings and all the people who have made that westward journey seeking something new. I thought about Fadl’s beautiful, but evidently difficult country, and the opportunities he was hoping for in America. And I thought of the immigrants in my own family, all but Sankar lost to the mists of time.

I have always considered these dear folks brave, noble heroes. But now I wondered about the kinds of decisions that they made in their bids for better lives. If I looked far enough back in my family history, surely I’d discover draft evasions, broken romances, and debts left behind with promises to make good later.

I could almost feel my mind expanding as my ancestors became more three dimensional.

None of our guides wanted to get close to any discussion of politics and of course we honored that. Moroccan authorities do not permit dissent. As we drove into Fez, we noticed a line of police cars heading in one direction, and Fadl commented that students at a nearby university were protesting the Israel-Hamas war. Large student gatherings must make the authorities nervous; it wouldn’t take much for a revved-up crowd to start chanting about repression close to home.

I am happy to report that Arab hospitality is alive and well, much the same as it was 45 years and 4,500 miles ago in Yemen. We received smiles and polite merhabas (hellos) from everyone and felt perfectly safe everywhere we went. When we paid vendors, often by simply holding out our hands full of unfamiliar dirhams, they selected one or two and then, just as we were turning to leave, hurried to place smaller coins, the change, back into our hands.

People on the street asked us if we needed directions, and pointed the way, often walking with us to make sure we didn’t get lost. In Dulles airport I watched a young Moroccan man spring forward out of the check-in line to help an elderly couple struggling to lift their suitcases onto the conveyer belt.

Our hotels were excellent. At each we were served mint tea upon arrival: glasses of green tea stuffed with mint leaves, and delicious cookies including an almond-filled delicacy called Kaab al Ghazal (gazelle’s horn).

Those delicious almond cookies, this time with coffee

Those delicious almond cookies, this time with coffee

Then, before we checked in, a staff member always took the time to sit down with us and answer our questions.

We found bathrooms clean throughout, and rest stops along the road were inviting and stocked, amazingly, with fresh pastries both sweet and savory, and cooked-to-order tagines.

One returns home full of thoughts and questions, and any irritations and disappointments we experienced in Morocco look different back in Minnesota.

Guides who were strictly professional would have probably been more pleasant. All three of our guys “cracked,” with impatience and seemingly irrelevant comments. But maybe their off-putting behavior had a purpose. Maybe they were guiding us, just not in the way we expected. Trying to give us a closer and more authentic glimpse of life in Morocco. And in that way, helping us know ourselves better. Isn’t that, after all, one of the reasons we travel?