On Friday afternoons when Sankar gets home from work, we consider the upcoming weekend with a kind of sheepish self-consciousness. We have no friends here and, even though we’ve been here less than two months, this seems to reflect poorly on us.

What are we going to do for the next two plus days? We’ve been to Istanbul’s major tourist sites more than once, and we either don’t yet know about or aren’t confident in our ability to get to the lesser ones. We don’t even have errands to do; I’ve already completed them with Umit.

Thankfully this August weekend is different: we have an invitation! Sankar’s Turkish colleague and his wife, both in their mid-thirties, have invited us to Bozcaada (Boz = earth-brown; Ada = island), just off Turkey’s Aegean coast. It will be a four-day weekend as Turks are observing the Zafer Bayram, Victory Day, commemorating the reclamation of Turkey from Allied Forces in 1922. We’ll leave for Bozcaada early Saturday morning, stay in accommodations on the island, and return to Istanbul on Tuesday. Even tonight we’ll be filled with purpose: packing our bags, throwing our Insight Guides in, and setting our alarms.

The term “Greek Islands” comes off the tongue with such familiarity it sounds like a single word. But the existence of Turkish islands is little known. Triangular-shaped, and fifteen square miles in size, Bozcaada is the smaller of two Aegean islands granted to Turkey in the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne. This finalized Turkey’s settlement with the World War I allies.

Bozcaada was called Tenedos by the Greeks and was long important because of its location at the entrance of the Dardanelles (known in ancient times as the Hellespont), the strait of water linking the Aegean to the Sea of Marmara, the Bosphorus and the Black Sea. Tenedos was where the Greeks hid their fleet in order to convince the Trojans that the war had ended—and thus to accept the Trojan horse. The island was involved in the 14th century Venetian-Ottoman conflict and served as a staging place during World War I.

With a year-round population of about 2,000, Bozcaada’s economy has been based on fishing, fruit, and wine since classical antiquity. 17th century travel writer Evliya Celebi, writing about Constantinople, commented, “The taverns are celebrated for the wine from Ancona, Sargossa, Mudanya, and Tenedos.” The island is also known for its strong northern winds.

The plan is for Sankar’s colleague to meet us on Saturday morning at a point on the E-80 highway just west of the Second Bridge. He and his wife have also invited two of their Turkish friends to join us. The four of them will be parked in a black Passat alongside the road. We will see them and pull over, and then our two cars will take off together.

I am flattered we are being included; this group is younger and would surely have a good time without us. It is an example of receiving a kindness here that I don’t know if I’d give: I would probably not invite a foreign couple along if I was going out of town with friends.

The highway meet-up goes as planned. After we pull up, Sankar’s colleague, trim and dark-haired, dressed in jeans and a sport shirt, gets out of his car and approaches ours. He hands Sankar a bag that includes fresh poğacas (savory, scone-like breakfast treats) and two bottles of orange juice. Another instance of kindness, and I think fast and pull out a bag of homemade chocolate chip cookies and give them to him. Guessing that chocolate chips wouldn’t be available in Turkey, I brought a large supply from home as well as two bags of brown sugar. Our hosts will comment on the cookies’ exotic flavor and ask for the recipe.

Our two-car caravan sets out, driving west through Istanbul’s diminishing sprawl and then along the Sea of Marmara. We are heading toward Greece and Bulgaria, but we will turn south before reaching international borders.

The piece of land we are on, wedged between the Balkans, the Aegean, and the Black Sea, is a historical area called Thrace. It is sometimes referred to as Rumeli, a word evocative of Rome, whose Eastern Empire flourished in Turkey for a thousand years.

Fields of sunflowers (for some reason, Turks call them ayçiçeği, moonflowers), grown for both oil and seeds, appear as soon as we leave the city. Soon both sides of the road are carpeted in yellow. The flowers stretch up gentle hills and into the horizon, their faces looking toward us as we move with the sun from east to west. I want to take a picture, but hesitate to stop both cars, and content myself with numerous shots from the car window, most of which turn out as yellow blurs.

After an hour, we pull over at a rest stop, a low, pastel-colored outlet mall with twenty or so shops, spic and span restrooms and, sitting on a new cement slab with spindly trees for shade, an outdoor tea garden. Sankar and I chuckle at the concept of an outlet mall, which we have heretofore considered solely an American phenomenon.

We sit down with tulip glasses of hot tea and meet our other two traveling companions, a divorcee in her forties with long chestnut hair, and her bearded, pleasant-looking 22-year-old son.

Then we continue south, through Şarkoy and onto the long Gallipoli peninsula that forms the western barrier to the Dardanelles. Fields of sunflowers continue, now on smaller plots slanting down to the Aegean.

This land was the site of World War I’s Gallipoli campaign, an intense naval and amphibious attempt by the Allies to capture Constantinople so as to gain a sea route to Russia. Many thousands of troops from Australia and New Zealand (referred to as Anzac forces) were sent to fight in this campaign, and over eleven thousand lost their lives under the hot Aegean sun.

Under the command of Mustafa Kemal, who would rename himself Ataturk, the Turks repelled both the naval and the land attack in a major defeat for the Allies. It was a defining moment in Turkish history as the motherland was saved, and it was also the beginning of national consciousness for colonial Australia and New Zealand.

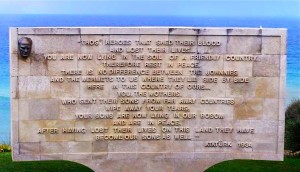

Memorials to soldiers from both sides dot the peninsula, and each April 25, families from Australia and New Zealand arrive to observe Anzac Day. In 1934, Ataturk sent the following message to Anzac mothers:

To those heroes that shed their blood and lost their lives . . . You are now lying in the soil of a friendly country. Therefore rest in peace. There is no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets to us where they lie side by side now here in this country of ours . . . you, the mothers, who sent their sons from faraway countries wipe away your tears; your sons are now lying in our bosom and are in peace. After having lost their lives on this land they have become our sons as well.

Near Çanakkale (çana = friendly; kale = castle), the peninsula’s largest town, we catch a ferry east across the strait to the mainland, and then drive south to Geyikli, where another ferry will take us out to the island. This convoluted route is hard to understand without a map, and as we drive Sankar and I reflect that, with our landlocked Midwestern sensibilities, we wouldn’t have been able to manage it on our own.

Now we simply follow our friends’ car without thinking. Our hosts are also relaxed, and we make a couple more stops, eating a magnificent “mixed grill” lunch at the Troia Palace restaurant, and stopping by the ruins of Troy, a World Heritage site grandly proclaimed by an impressive sign and a faux wooden horse representing the one the Greeks hid in, but actually not much more than a rectangular mound of earth and several large clay amphorae.

Still, it is Troy, and we walk around hoping to catch the mood of ancient warfare and treachery. Finally we look at our watches and exclaim at the time. Only a half hour until the ferry leaves! We get back in our cars and zigzag with alarming speed through a series of tiny Aegean villages, making sharp turns on narrow, paved roads.

When we finally arrive at the pier, a white sedan we’ve been following hesitates, and our two cars edge past it and into the line of cars waiting to board. We end up being the last two vehicles allowed on this, the last ferry of the day, and for the entire weekend we joke about how “the guy in the white car” is surely angry and coming after us for revenge.

We received the invitation late, and this is a holiday weekend, so we are not able to stay with the group at their hotel. No problem; we’ve reserved a room at Hotel Katina only a few cobbled blocks away in Bozcaada Town—a picturesque grid of whitewashed one- and two-story dwellings with shallow-pitched red roofs and brightly-painted doors. We walk with our bags through its miniature streets. Alongside each dwelling sit wooden tables covered with tablecloths: instant family cafes, waiting for dinner occupants.

Hotel Katina is a two-story, hundred-year-old residence. Its windows feature blue grillwork and hanging flower baskets, and one of its outside walls is covered with grapevines that wind their way via an electrical line across the street and down the wall of a smaller building. Inside, the rooms are decorated in an incongruously sleek Euro-modern style that we will discover is quite typical in Turkey.

The six of us reconvene for a dinner of grilled fish at tables set up just a few feet from the wharf. The weather is warm and the sky a deepening violet. We are so close we can almost touch the colorful fishing boats that bump and jostle each other, making the silvery water splash upward. The physical separation of the island is facilitating our mental separation, and Sankar and I can finally relax. We will sleep well here, and wake feeling none of the jarring unfamiliarity that has been our companion all summer.

Each morning after breakfast, our four companions head to the beach. They return at lunchtime, only to set out for the beach again in the afternoon.

Two beach trips in one day seem like a lot of sun to Sankar and me, and we don’t want to overburden our hosts who, without us, can chatter away in Turkish. So we decide to stay back in the mornings. We have brought a couple of Turkish language textbooks written by a UCLA professor named Kurtuluş Öztopçu, his very name seeming to embody the difficulty of Turkish. The two of us sit at a little wooden folding table outside the hotel’s front entrance taking notes, watching the few passersby and smiling at the hotel’s namesake, Katina, as she bustles from the hotel proper to the vine-covered breakfast room across the street. This middle-aged dynamo is definitely the family powerhouse; her husband spends mornings at a teahouse down the street, sauntering home only at lunchtime.

Perhaps Katina senses our watchful neediness—despite some kind friends, we feel bereft, marooned here in Turkey—because she frequently stops her work to chat or to ask us if we want a pastry her bake staff is pulling from the oven. And one morning she walks up to us with an emphatic story in rapid Turkish that finishes with a laugh. Thanks to the timely arrival of an English/Turkish-speaking couple, we get the translation. Katina has had a dream about us—and in Turkish lore, that apparently means we are thinking about our mothers. Sankar melts, “We have the same saying in south India!”

Late Sunday morning we leave our books and set off by ourselves to explore the gray stone castle/fort that guards the harbor. It is long and relatively low, with crenellated walls interrupted by squat, hexagonal towers. We walk through weeds around it, reading in our guidebook that the Ottomans built it on a spot formerly used by Phoenicians, Genovese and Venetians. We reflect on Turks’ reputation for ferocity and decide that, with 5,000 miles of exquisite, strategic shoreline, it is fully justified.

A bored guard ignores us as we duck under a stone arch and enter the keep. We climb to a balustrade for a view of the tiny, curving harbor, feeling the gusts of wind the island is known for.

On Monday morning, our companions take us to breakfast at a nearby inn called Maya. The place, hidden behind an ordinary façade on a nearby street, offers a typical Turkish breakfast—olives, tomato slices, white cheese, boiled eggs—served in an enclosed outdoor garden, but is well-known for its extensive variety of homemade fruit preserves, eaten on bread pulled fresh from a wood oven. Indeed, several tables in the middle of the courtyard groan with a sticky paradise that includes standbys like strawberry and cherry, but also tomato, fig, lemon, rose, sweet pepper, mulberry, and ayva (quince) jams.

I don’t care deeply about jams and jellies, but pride in homemade preserves is “a thing” here, a cultural tidbit we are picking up thanks to our companions. Their eagerness to teach us about Turkey is one part an effort to deepen our friendship and two or three parts an expression of their intense love for their country.

I am beginning to see that, while some countries modernize and leave old customs behind, Turkey maintains a firm sense of its historical self. We are learning that Turks have a distinctive cuisine for every meal of the day and we will soon encounter peculiar beverages such as sahlep, a hot drink made from dried orchid roots, and boza, a fermented bulgur brew sold in the evenings by men who walk the streets with copper pots yelling, “boza.”

Each region in Turkey has distinct songs; indeed one evening soon we will poke our heads into a traditional Turkish meyhane, tavern, and listen to a chorus of Turkish men lifting cups of rakı, anise-flavored liquor, and singing mournful-sounding Arabesque folk songs.

Most of these customs, though different, do not seem strange; indeed they seem to echo our own culture’s past, which also contained preserved foods, folk songs and root-based drinks. Perhaps by getting to know Turkey, we will come to know ourselves better. At this point, I want to know everything.

In the afternoons, tubes of sun cream in hand, we head with our hosts to the beach. We pay a small fee to enter and occupy spots under charming pale blue wicker umbrellas. The water is warm and shallow, the sand soft, and the sea deep azure blue. In the distance we can see the craggy hills of the mainland.

In contrast to my female companions who wear bikinis, I wear a sturdy one-piece suit. Sankar wears some new trunks he’s had to buy from a shop near the wharf. They are long and droopy, their fabric patterned with beach scenes, and we tease him about his “partay” duds. We sit with our friends in the sun, reading and dozing.

Leaving the beach, we drive the long way around the island, noting its barrenness and modest-sized rocky cliffs—were the Greek ships hidden behind these?—and stop at one of twelve wind farms, pausing to read signs describing how much power is being produced for Turkey. Then at the southern coast, we stop in at Corvus, the most prestigious winery in Turkey. It is startling to walk into a large, modern tasting establishment and realize that the gentlemen standing at the long counter, ready to pour, are all Muslims. We sample the same cabernet sauvignon that President Obama was served on his 2009 trip to Turkey, and purchase a few bottles to go.

Sun-dazed, after a rest, we reconvene in the early evening, and walk to one of the island’s restaurants. Under the shade of a huge plane tree, we eat pasta and more grilled fish, and sample deniz borulcesi or sea beans, long green segmented stems, not much thicker than cooked spaghetti. For dessert, a local delicacy: poppy syrup sorbet, tart and gingery, made with red poppy petals.

With the loneliness and challenge of Istanbul far away, Sankar and I can shine in our role as grateful guests, new kids in town to whom much can be explained. We ask questions in tandem, nodding to each other as we take note of new information. We exclaim our interest in future trips: one to southeastern Turkey is mentioned and will materialize in the fall. When something challenging is said—a comment that Turkey’s Kurds “. . . don’t want to work”–we remain silent, saving any analysis or re-hash for when we are alone.

These newly discovered social skills—questioning attitudes, intent listening—are both pleasing to us and promising.

One evening after dinner, I bring up the topic of our surprise at Turkey’s gleaming prosperity. “I don’t claim to know much about Turkey,” I start. “But it has a reputation for being—well, poor—and I’m guessing that reputation was true not too many years ago. What happened here to change all of that?”

Our companions are quick to answer: “Turgut Özal. He opened up the economy in the nineties, allowing more foreign investment.” They go on with specifics. I have heard the man’s name before and will look it up when I get back to Istanbul.

All too soon Tuesday morning arrives and we pack up for the trip back to Istanbul, hugging Katina goodbye, driving our two cars onto the ferry, and watching the little island recede as the boat approaches the mainland. We head back up the Hellespont, the water first on our left and then, after the second ferry, on our right.

Ever the good host, Sankar’s colleague has planned a final treat, a dinner stop at Tekirdağ, a town renowned for its kebabs. The six of us enjoy delicious, salty grilled lamb and peppers at the town’s best restaurant, our skin still flushed from the island sun. Then we glide east alongside the Sea of Marmara, the setting sun blending sea and sky together into a pale blue haze.

The trip has been unique. It has refreshed us and readied us for another run at Istanbul. It has given us some glimpses of Turkish culture—and Turkish hospitality. I am beginning to see that the Turks are wise and charitable in the ways of friendship, and I wonder if something in their upbringing, perhaps something more communal than ours, gives them this ease.

The sky is black as we approach Istanbul, but the city lights set the entire horizon aglow.