Dear readers, A bunch of you have asked me where I am currently. I’m home in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Through this site I am blogging about the years I lived in Istanbul: 2010 through 2013.

I was enjoying my thrice-weekly Turkish class. My classmates included four Japanese women, wives of engineers directing construction of a transportation tunnel between the city’s European and Asian sides; a young Polish woman who was engaged to a Turk; and Annika, my Swedish friend from the first class. Our teacher Ferda, my former tutor, was warm and encouraging, and seemed, despite our constant errors and mispronunciations, to comprehend most everything we tried to say. Having Ferda boosted my confidence, and I felt increasingly comfortable using Turkish while out and about.

The class would be ending soon, however. I wanted to keep moving forward with Turkish, and indeed I could take more classes. But what I really wanted was a meaningful, regular way to engage with the Turkish culture. Increased use of the language would, I felt, follow that.

Sankar was busy traveling to The Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary, Romania, Russia, South Africa, and Dubai. In November he was heading back to the States to teach a leadership development class for 3M. He loved those teaching interludes. “Maybe I will teach a class or two when I retire,” he mused. His life was in full gear.

Although I wanted to be happy for him, in private I seethed. Before we moved to Turkey, I had embarked on a teaching career, teaching freshman composition at a small college in St. Paul. I had enjoyed it, and would have loved to continue. But instead, here I was, stuck in first gear, weeks and months ticking by. Resentment building

Would I ever get back on some kind of professional track? My chances didn’t look good. In America, The Great Recession continued. Online, I read over and over again about middle-aged professionals who had lost their jobs. News articles described gray-haired citizens applying for dozens of jobs with little success, their professional lives seemingly cut prematurely short. They warned that job seekers in their fifties or older might well consider themselves permanently sidelined. Already feeling professionally insecure, and living in an even more youth-oriented environment than the States, I was struck by this message. It was easy to conclude that I might never hold a job again. And it wasn’t the faceless recession I had to blame; it was 3M and my husband.

I wanted a job! This negative news, and my envy of people busy working made me put an ever higher value on employment. Employment in Turkey would give me status. It would ward off boredom and resentment. It would be the answer to my problems. I was sure of that.

Sankar listened to my concerns, no doubt feeling a bit of guilt. To his credit, he had no qualms about the idea of me working in Turkey, no concern that my taking a job might make his life less convenient. Skilled at calling up resources—and out the door for another trip—he turned to his secretary, Didem, asking if she could help.

Didem was turning out to be a fabulous secretary, if indeed that title was big enough to encompass all that she did. Creative and full of initiative, she seemed to embrace our current neediness. She had, in addition to her normal duties: downloaded manuals so I could figure out how to use my apartment’s appliances, obtained an extra pass into the U.S. embassy grounds for our nephew, Jon, for its July 4th celebration; facilitated our health club membership; helped me enroll in Turkish classes; found an English-speaking dentist for us; appointed an honest, energetic cleaning lady to help us keep up with rigorous local standards; and even helped Sankar cast a last-minute vote in the U.S. midterm elections.

Didem’s motivation? Sankar had championed hiring her, and she wanted to prove herself. And, since he was often away and unaccustomed to having a personal assistant all to himself, the amount of other work he gave her was light.

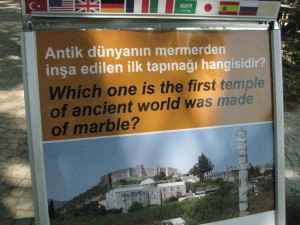

Now Didem called and asked me what kind of job I wanted. I had a small editing business back home and had noticed that English signs, menus, and labels at Turkish museums were quite often misspelled or grammatically incorrect. I’d been shocked when visiting Ephesus, Turkey’s most popular tourist attraction and a UNESCO World Heritage Site, to discover that the main sign at the entrance, professionally produced and surrounded by high-quality photographs, read:

I had heard visitors snickering at these kinds of mistakes, and I knew this would appall the Turks, who perennially felt looked down upon by other Europeans. I was on Turkey’s side. I wanted to help make its signage perfect.

I told Didem I would love to be hired as an editor with the tourism bureau, but that I had recently taught English and would consider that kind of job as well.

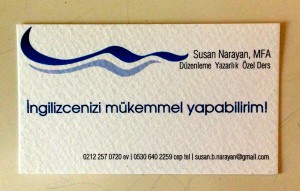

Didem started by taking me to a graphic design firm for help producing business cards advertising my editing skills. The new card was turquoise and white with an icon depicting waves on water, and read, Ingilizcenizi Mükemmel Yapabilirim! (I can make your English perfect!)

Didem encountered an advertisement for English tutors—I am not sure where—and called the number listed. She reached a young American graduate of Northwestern University who was living in Istanbul because he had married a Turk. The guy, Ian, gave private English lessons and was looking for some associates to work for him.

“I have a good feeling about him,” Didem told me. I called Ian and the two of us met for coffee at Gloria Jean’s coffee shop in Ortaköy (orta = middle; köy = place), halfway up the Bosphorus.

Ian told me his clients were mostly businessmen whose jobs required better English, and he invited me to join his group. A week later, he held a meeting with me and two other new associates to explain his teaching philosophy. I thought the meeting went well and I awaited assignment—but never heard from him again.

At this point, Didem explained the difficulty of matching me up with the folks who wrote the signage for the country’s tourist sites. “These are government ministries,” she told me, grimacing. “They won’t be interested in outside help.”

Secretaries can be many things, but most are not creative freethinkers that take wide latitude in doing their jobs. Didem was an exception. She now began writing to Turkish universities on my behalf. I had given her some ideas, but I didn’t really know what she was putting in the letters. How was she describing me? Was she inflating my credentials? It felt like a dream to have someone assisting me with such a tedious, potentially discouraging task, and I didn’t ask for details.

Didem forwarded to me an online application from Sabanci University, one of Istanbul’s most prestigious private schools. I clicked it open only to discover that the very first question on the cover page, even before name and address, was “How old are you?” “Ancient,” I thought, and set it aside.

She followed up her letters with phone calls, and one day she informed me that a woman named Nazan Gökay at Yeditepe (Yedi = seven; tepe = hill) University had agreed to meet with me and chat about opportunities. I contacted Nazan and we set up a meeting at another waterside café in Ortaköy.

Nazan was a partially-retired English teacher with dyed-scarlet hair, who looked to be in her late sixties. After pleasantries, she asked me if I’d be interested in working as a prep teacher, and I asked her what that meant. Her answer opened up a world of possibilities.

She told me that nearly all universities in Turkey teach their classes in English. But, because of less-than-optimal high school English teaching, most entering college students don’t have the necessary language skills to begin their coursework. They have to pause—some for up to two years—in order to become proficient enough at English that they can do college work.

This situation provides a huge opportunity. Programs called hazırlık, prep, are attached to every university, and employ a veritable army of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teachers. Would I be interested in working in a prep program? I certainly would. I didn’t have EFL teaching credentials, but surely, I thought, I could provide assistance with student writing.

How fortunate are those who hear Opportunity’s knock. There, sitting alongside the Bosphorus with a stranger, my life’s direction changed. For the first time, I started thinking about teaching English to those who didn’t speak it.

Didem now began targeting her letters to prep programs in Istanbul, using a list I gleaned from Nazan and the Internet. She also contacted regular college English departments. We avoided public universities even though they were considered more prestigious, because schools under government control had strict and often arbitrary rules. For example, you could only teach something that had been your college major. In my case, that was nutrition.

Many of Turkey’s private universities were new, established to help educate a baby boom that had just reached young adulthood. Although they were a great deal less prestigious, they were less stringent in their faculty requirements. Within a couple of weeks I had interviews set up at four of them: Bilgi, Kadir Has, Koç, and Özyeğin.

I went first to Bilgi, which means “information” in Turkish. The university, founded in 1994, was located in a modern, yet shabby part of Beyoğlu north of Istiklal Avenue. Ümit told me the neighborhood was not particularly safe, but that it was improving, and indeed a new-looking police station sat right across the street from campus. Inside, I met with a friendly American woman who was in charge of Bilgi’s writing center. She told me they were not hiring at the moment, but asked me to get in touch again the following spring.

Kadir Has University, founded in 1997 and named after a banking and automotive industrialist, had two campuses, one in the Old City and the other near the airport. How cool would it be to work in Old Istanbul, I thought, imagining an office in an Ottoman era structure facing the Sublime Port, its roof like a wide-brimmed hat, the underneath decorated in gold leaf. Alas, my appointment, late on a Tuesday afternoon, was at the other, airport campus. Ümit and I drove for almost an hour through heavy traffic to reach the nondescript-looking neighborhood and locate the exact address.

I walked into a large, carpeted office to meet my interviewer, who was talking on the phone. Perhaps she was finishing an unpleasant conversation because she looked at me crossly after she hung up, and failed to begin with typical small talk. She asked sharply whether I wanted to teach freshman composition or ESL. I don’t know why I didn’t tell her I was interested in both, but “ESL,” came out. It was the wrong answer.

“Why did you come here?” she snapped. “This is the English department.” Intimidated, I couldn’t think of any way to backtrack, and after only a few minutes I thanked her and excused myself.

How could I face Ümit so soon after all the time it had taken to get here? I ducked into a nearby bathroom and hid out for awhile before finally trudging outside to the car and making a lame excuse. Ümit’s silence on the way back seemed to say, you’ll never get a job here in Turkey. Although I wouldn’t have been able to find the place without him, it was one of those times when I sorely wished I could drive myself home, licking my wounds in private.

Prestigious Koç University, founded in 1993 and named after Vehbi Koç, one of the wealthiest men in Turkey, was located on a huge expanse of land overlooking the Black Sea, about twenty miles north of Istanbul. With its brand new red brick buildings and gleaming cherry wood interiors, the place reminded me of a fine new restaurant that was trying to look old and established. My meeting was with a stocky, round-faced man named Patrick Campbell, originally from Alabama. Campbell was polite and welcoming, but only a few minutes into our meeting he launched into a tirade about the Koç students’ immaturity and unwillingness to do any work. This mini-rant, though apparently honest, was striking.

I met another American, a woman who was in charge of Koç’s English department. She had an opening for a faculty member, and I hurried to apply, assembling transcripts and recommendation letters, but alas, my one semester of teaching was too meager to make me a serious candidate.

Finally I went to Özyeğin (ouz YAY en) University, founded in 2007 and named after Hüsnü Özyeğin, a banking billionaire and Harvard Business School alumnus. There seemed to be a pattern here in Turkey: billionaires starting universities and naming them after themselves. I winced as I read Özyeğin’s home page: “Özyeğin University is the 4th Best University in Turkey Among Universities started after 2005.”

The school’s lone building was modern and elongated, with floor to ceiling windows. Inside, a young man named Rifat escorted me in and a secretary appeared and offered me a tulip glass of tea.

First I met separately with two women, the head of the department and the director of instruction. As they explained the university’s prep program, on of them apologized that she had a cold, and took a tissue from a box on her desk. Oddly, she then proceeded to hold the tissue for several minutes, still folded, under her nose. Then she put it down, but a moment later she unfolded and stretched it over the lower half of her face. It was interesting to watch her manipulate the tissue, all the while asking and answering questions, but never actually blowing her nose.

The two women asked me how many hours a week I had taught back in the States at Hamline (they pronounced it Hahm LEE nay) University. “Three,” I replied.

“Well, this job is twenty,” they told me.

That information didn’t really sink in—twenty hours sounded like a part-time job. And even if it had, I wouldn’t have questioned it. Getting a job was going to provide meaning to my life here; it was going to prove I wasn’t washed up, as it seemed so many of my generation were, back in the States. I did realize, however, that the job would involve teaching reading, listening, and speaking, not just writing.

One question to me was, “What if you have given a homework assignment and then prepared a follow-up class activity and the students come to class without having done the assignment?” This stumped me, and I recalled Pat Campbell’s complaints about the laziness and immaturity of Turkish students. Thankfully, they didn’t seem to be looking for a specific answer as much as asking what I might do to motivate my students.

The next step, I was told, would be for me to come back and give a PowerPoint presentation on my teaching philosophy. I gulped, but then remembered I had prepared a philosophy statement in a pedagogy class I’d taken several years ago.

The following week I returned to Özyeğin and gave my presentation, discovering at that time that one of its ESL teachers was resigning at the end of the semester and another would be starting maternity leave in the new year. Several follow-up questions that began with “If we were to hire you. . .” seem to confirm that my chances of employment were good.

The fact that this job would be more about my English ability than any hoped-for progress with Turkish didn’t bother me. I’d be working for a Turkish organization, after all, with Turkish colleagues and supervision.

The several weeks I’d spent interviewing had filled my time, providing an exhilarating challenge on the days I wasn’t in Turkish class. But then they ended, and I heard nothing. Ten days went by, then two weeks. I became snappish at home, and I remember a tense weekend in which Sankar and I said little to each other.

Now another possible roadblock arose. I began hearing from friends—both Felicia and Annika—that foreign spouses were not allowed to work in Turkey. That if one member of an expatriate couple held a job requiring a work permit, a permit would not be issued to the other. I had been clear in my interviews, however, that I was in Turkey because of my husband’s job, so this new information left me confused.

On a mid-December morning about two weeks after my Ozyegin interview, our Turkish class was on a field trip to Kadiköy, a charming university town on the Asian side of the Bosphorus. Ferda had met the seven of us at the ferry terminal, and conversing in Turkish, we had followed her through the fashionable seaside neighborhood of Moda and the streets of downtown Kadiköy, with their quaint candy shops, fish and vegetable markets, and gourmet food shops.

As we filed along the busy streets, my Turkish cell phone rang. I was not yet used to this new device, purchased to avoid having local callers pay international rates to talk with me, and I fumbled to answer it. With a truck full of Turkish pumpkins rumbling by, I didn’t quite catch the caller’s name, but I did understand that I was being offered a job. At the end of the brief conversation, I had to ask, “Is this Özyeğin?”

“Yes,” was the reply.

I was so surprised and pleased that I felt almost breathless, and decided not to say anything to my classmates that day. My life was going to change dramatically. No more lolling around the house and inventing errands to go on with Ümit. No more dutifully attending Turkish lessons and wondering when I’d ever use the ettirgen verb tense. No more Turkish classes at all. When 2011 started, I’d be gainfully employed!

I called Didem and thanked her profusely. She had spearheaded this search, creating something where there had been nothing. I wouldn’t have gotten the job—or come close to getting any job—without her. I was so impressed that I gushed to Ümit, “In the States, Didem wouldn’t be just a secretary. She’d be running her own business. She’d be rich.” But, although he quite liked Didem, he sniffed and shook his head in disagreement.

On our next class day, when I told her my news, Annika’s face fell.

“I’ll still see you,” I tried to reassure her. We had gotten together for dinner several times with our husbands.

“There will be less contact,” she said stiffly. I felt bad, but vowed to keep in touch. Annika was my first friend in Turkey, member of a tiny, exclusive club.

Felicia simply shook her head and remarked, “You’re going to have a terrible social life.”

In the space of just a few months I’d gone from student to teacher. And as I prepared to go home for Christmas, I received two holiday invitations, one for dinner at the home of 3M Turkey’s Managing Director, and the other from Joy, a fellow newcomer, for a holiday brunch. My social life, moribund for months, had begun to come alive.

And Sankar and I had something to look forward to when we returned. My Polish classmate, Ana, had invited the whole Turkish class to her wedding. It would take place on New Year’s Eve at the Four Seasons Hotel. The same hotel we had stayed in during our look-see visit. We’d now be arriving as invited guests.

It looked as though my life was shifting into higher gear.