Sankar and I stand facing six huge, stone-carved heads. Above us are terraces containing the carved bodies to whom these heads once belonged. It is a scene of drama and grandeur, but also destruction.

We are spending three days in southeastern Turkey, gliding from the Roman era back to pre-history and then forward to the Biblical period of Abraham. The occasion: another American Research Institute in Turkey (ARIT) tour. Our itinerary: the World Heritage site of Nemrut Daği with its larger-than-life sculptures; the Neolithic excavation of Göbekli Tepe; and the town of Şanliurfa, birthplace of the prophet Abraham.

ARIT, that fusty-sounding club I signed up for at the international women’s meeting a year before, was turning out to be a real winner. Every two or three weeks the group offered a trip to an interesting, off-the-beaten-track site, as well as access to an interesting group of Turks and expatriates.

I had toured Istanbul’s Seventh Hill with ARIT one Sunday while Sankar was out of town. Fascinated by all that I saw, my dismay at spending a weekend alone had vanished. That was the first time Turkey had dazzled me out of my mundane problems, but it wouldn’t be the last.

Sankar and I both attended the next ARIT event, “Ottoman Tombstones,” standing in drizzle high above the Bosphorus looking at graves dating back a hundred and fifty years. We learned that Turkish graves employ both head and foot stones, and that the Ottomans sculpted turbans on male tombs and floral reliefs on those of women.

Another ARIT trip took us to what would later become the Istanbul Naval Museum. There we gazed at an eye-popping assortment of “caiques,” narrow, decorative wooden boats that Turkey’s sultans used for Bosphorus excursions and ceremonies. Their slender prows intricately carved, these fairy-tale crafts were up to forty meters long, but only two meters wide. As many as two dozen rowers powered the boats while the sultan and his retinue lounged in cabins of ivory, tortoiseshell, and mother of pearl.

I had long been skeptical of group tours, thinking them either for the timid or for those who couldn’t be bothered to do their own planning. But ARIT was introducing us to parts of Turkey we’d never heard of. And in some cases, it was giving us access to places like the Naval Museum, which wouldn’t open to the public for several years. Another reason we enjoyed touring with a group was that, after over a year in Turkey, our social life was still rudimentary.

Sankar and I had gone out to dinner a few times with my friend, Annika, and her husband, whom we both liked. But the evenings were always a bit negative, as they were not enjoying life in Turkey.

Felicia and I saw each other every month when we rode the bus to our book group. But her husband, Andy, an English teacher at Robert College, had an array of smart, interesting colleagues, and they were often busy with that group.

Another potential friend was Mia Preston. A friendly Texan about my age, she had moved to Turkey from Dubai with her partner, David, an oilman. David was always traveling to Iraq and other hot spots, and had lots of insights (presciently in 2011: “Yemen is coming apart at the seams.”). We’d had dinner together several times, but they maintained an apartment in Dubai and were often away.

Thus we stood eagerly one Saturday morning with the ARIT group at Sabiha Gökçen, Istanbul’s Asia-side international airport. After a short flight, we landed at the sparkling little airport in Şanliurfa, a small city not far from the heavily guarded border that separated Turkey from Syria, six months into civil war. We had glimpsed Şanliurfa, on a day trip from Gaziantep a year before with Gökhan and Burcu,

Named Edessa by Alexander the Great, Şanliurfa has been a part of recorded history since the 4th century BCE. The city was known as Ur of the Chaldees and then Urfa. To honor its resistance to the French after Turkey’s 1920s War of Independence, Urfa was allowed to attach şanli, meaning glorious, to its name. Despite the military prefix, the town’s history is actually peaceful. In addition to Abraham, the prophet Job is also believed to have been born in Şanliurfa.

We boarded a small tour bus, taking a seat in front so we’d be sure to catch everything our guide had to say. As we set out, she introduced herself: Çiğdem (the word means crocus) Maner, a pretty German-trained doctor of archaeology.

Through the bus windows, we peered at the vast, open landscape of southeastern Turkey: dry grassland interspersed with barren patches of soil. Brown mountains reclined in the distance. The ground was pale, but where crop remnants had been burned, it was the color of chocolate.

Çiğdem explained that we were on the land between the Tigris and the Euphrates rivers. She told us that in Greek, the word “between” is meso, and the word for “rivers” is potamia. Thus our location: Mesopotamia.

Mesopotamia. Cradle of civilization. The word held mystery and romance in its very syllables: Me so po TAY mia! A place of DRA ma!

Çiğdem commented on the barrenness around us, telling us that the ancient Romans and another group, the Commagenes (the name means “cluster of race or offspring” in Greek) had cut down Mesopotamian forests for charcoal and timber, and had overgrazed their flocks. The result had been severe erosion that, she told us, extended south and east into Syria and Iraq. When rivers silted up with eroded soil, floods became more likely. According to Alan Grainger of Leeds University, a human-caused flood occurred in Ur in about 2500 B.C. Eroded soil, or silt, also caused rivers to become higher than the land around them. Water then overflowed onto fields and when it evaporated, it left mineral salts in poisonous concentrations. This was recorded on Mesopotamian cuneiform tablets.

Grainger writes, “It is no coincidence that many ruins of great temples and palaces are today found amid sandy wastelands. And as I looked at the terrain, I recalled the words of New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman, who believes that environmental distress and degradation are the cause of many world conflicts.

The eye searches for exceptions. I noticed that whenever there was a small farm or a tiny pool of water, the land was a bright, luxuriant green. Otherwise, the tan of the grasses washed to butter yellow in the sun and, in rare patches of shade, darkened to orange-brown. Scrubby brown vegetation covered the mountains, rubbed away in places to reveal white rock. I had to look twice to convince myself it wasn’t snow.

From time to time, spindly, brittle-looking trees came into view, planted in diagonal rows. Their trunks seemed barely able to support their crowns, and the ground between them was a bright coppery brown. These were pistachio trees. I wondered how they got the water they surely needed. We passed fields of low green plants covered with white tufts: cotton, and olive groves were also roadside companions. A flock of shaggy black and brown goats trotted across the highway, kicking up dust and urged on by an elderly keeper wielding a stick.

And then like a mirage, a bright blue, startlingly translucent body of water. It looked like a medium-size lake, but its far edge extended into a valley and then disappeared. It was the Euphrates, river of life, site of Eden. This river begins, Cigdem explained, in the mountains of southeastern Turkey and makes its way through Syria and Iraq before emptying into the Persian Gulf. We stopped talking and stared.

The contrast between liquid and near desert was stark. It was difficult to imagine this land as it had been two millennia ago, shady and fragrant, lush and damp.

Back in the bus a few minutes later, we pulled off the road at a sign that proclaimed, “Neşet’in Yeri [Neşet’s Place] A Restaurant by Lake.” The proprietor and his family greeted us and we sat down at tables along the water’s edge. Then they began bringing out plates of food on enormous metal trays: charcoal-grilled chicken and lamb surrounded by curly-leafed lettuce, parsley, and tomato slices. Plates of flat bread. And sliced onions roasted in shallow clay pots, their tops blackened from the fire.

Now we had a chance to talk with our tourmates. John Chandler, headmaster of Robert College, and his wife Tania. Elaine and Peter Graham, South African-British retirees, both carrying impressive cameras. Hugh Pope, a handsome, young-looking writer—later I’d discover he’d published several histories of Turkey—along with his wife and three young daughters. Laura Sizemore, a congenial thirty-something New York lawyer who visited Istanbul on business every month. How, I wondered, had she found her way to ARIT? Laura had been sitting behind us on the bus, reading the previous Sunday’s New York Times and kindly passing sections up to us. Alison Stendahl, a sixty-something blond from Edina, Minnesota, who had lived in Istanbul for over a quarter century. Neil Korostoff, a professor of landscape architecture from Penn State, who had just arrived on a Fulbright scholarship. Linda Caldwell, a vivacious embassy retiree who spoke fluent Turkish. Linda had already recommended two books on Turkey.

Experience and language skills are coins of the expatriate realm, and many of these new acquaintances had lived for years in Turkey. Sankar and I were, by contrast, mere infants, and our faces shone with admiration. Sankar was likely to display his enthusiasm by calling out, “Hey, Sue, come over here and meet . . . !”

Busy now with jobs, Sankar and I had passed the stage of guilt and resentment that plagues new expatriates. But sometimes Sankar’s enthusiasm overflowed into hyperbole. When he was asked what he did and proclaimed, “I have all of the Middle East and Central East Europe, as well as South Africa,” I cringed, fearing his boasts would put off potential friends.

Now, as we sat and ate, Sankar was busy talking with people on his left side. To my right, Peter was holding forth in his British accent, and Neil was joining in, his responses academic. I half-listened, taking in the dazzling river and the simple, splendid food.

Finished with lunch we headed for Mount Nemrut to see statuary and graves built by the Commagenes. The name Nemrut refers to King Nimrod, grandson of Noah, a proud, vengeful man mentioned in the holy books of all three monotheistic religions, whose rule dated back to about 2,100 BCE. In about 883 BCE, the Commagenes appeared from the east, fighting off the Persians and Alexander the Great. Finally, in 109 BCE, they became independent under King Mithridates, ruling an area the size of Switzerland.

Mithridates’ son, king Antiochus I, ruled for 33 years and traced his ancestry to both Alexander the Great and the Persian Seleucids. To commemorate this, he chose Nemrut, the highest mountain in the area, and built a mountaintop terrace, leaving space for his own grave near its peak. Then, on three sides of the mountain, he erected enormous, seated throne-like statues weighing up to nine tons each, out of limestone. One side depicted his Greek heritage, another his Persian ancestry, and a third is indeterminate. He also added animals—lion and eagle statuary—and inscriptions.

The bus took us halfway up the mountain, and then we set out walking on a gravel path. The air was dry and comfortably cool as we headed toward the Eastern terrace, made of shale. There are six heads on this terrace, including Apollo Mithras; Zeus Oromasdes; Antiochus I himself; Heracles-Ares, and two others, assumed to be lesser Greek gods. Each head is about eight feet tall and rests right-side-up amidst rubble. The carving is both simple and skillful, the faces attractive and strong-featured. Atop most heads are conical hats, some of which have lost their points, and the men have curly beards. Our guidebook referred to these huge stone heads as “Turkey’s answer to Easter Island,” but the simple, clean lines reminded me of Scandinavian sculpture.

I wondered what Antiochus had put his people through to build these statues. What kind of arrogance drove him to order their construction? But thanks to him, two millennia later, evidence of his plucky tribe was still here for all to see. I couldn’t help but admire that.

After viewing the sculpted heads, we climbed up to view the row of six bodies they had originally belonged to. There they sat, frozen obediently in place near the barren summit, their heads, cowed and tumbled, below. An ironic result of the passage of time—or perhaps the work of iconoclasts.

As we wandered the ruins, the sun began to set, breaking up in pinkish-yellow rays that bathed the statuary. The air began to take on a chill and both the sky and the creases of the nearby mountains turned a deep, almost navy blue. The ground itself became the color of cocoa.

Another day on the mountain, just like thousands before it. We stood in the sunset for some moments, surveying Mesopotamia, and the Euphrates, a shining ribbon in the east. The lengthening shadows and chill were bringing our time on the mountain to an end, and I felt a pang of regret for the larger passage of time. How I wished I were twenty years younger so that I could develop some mastery in this part of the world. Or that I had another lifetime that I could devote to studying Turkey and Turkish, and figuring out all that had happened on this land. Was some of Antiochus’ lust for immortality in the mountain air?

The sun finally dipped below the horizon and we walked down the chocolate hill toward the warm, waiting bus.

The next morning in the hotel, we sat with John and Tanya Chandler for a Turkish breakfast of tomato slices, bread, and honey. John, a regal, silver-haired man, had led Robert College for seven years, and before that had directed highly-regarded Koç high school. In only a few months, he would retire and leave Turkey to set up house on the coast of Maine. As we talked, Tanya grimaced in anticipation of the transition ahead, but I guessed the move—particularly the shedding of professional identity—would be harder on John.

After breakfast we drove to Göbekli Tepe, an archaeological site dating from the Neolithic Era (10,000 – 2,000 BCE). Göbek means belly in Turkish, and tepe means hill. Göbekli Tepe was discovered by German archaeologist, Klaus Schmidt, in 1994, when he noticed a hill with a bulge in it. I guessed that the bulge might have been more noticeable because of deforestation, but how, I wondered, does a foreigner go from noticing an unusual shape to getting the permits and workers to start taking it apart?

Over the years, archaeologists had removed layers of debris from Göbekli Tepe, revealing twenty circular arrangements of T-shaped stone pillars. Carved of limestone, each pillar weighed about ten tons, and many featured reliefs of dangerous animals: lions, foxes, snakes, scorpions and vultures.

Göbekli Tepe pre-dates Stonehenge and the invention of writing by about six thousand years. It contains no evidence of human occupation—no dwellings or cooking debris. Schmidt and later archaeologists surmised that Göbekli Tepe was a kind of Stone-Age place of worship: a holy place or “cathedral on a hill.” If so, this would make it the world’s oldest known religious sanctuary.

Çiğdem told us that, prior to uncovering Göbekli Tepe, archaeologists believed that humans constructed religious sites only after they had settled down into farming communities. They believed that mere hunter-gatherers neither had the time nor the skills to produce monumental complexes. Göbekli Tepe changed that. Now archaeologists believe that efforts to build holy monoliths—organizing and dividing labor, and obtaining resources for spiritual purposes—pre-dated and laid the groundwork for the development of more complex societies.

Wooden boardwalks surrounded the site, and ladders allowed workmen to move between the levels. Schmidt having retired, the site leader was now a handsome young German with wild curly hair, wearing a leather vest and leggings. He stopped and explained to Çiğdem in German what was currently going on. We stood in the midday sun as she translated for us, trying to imagine the sanctuary full of Neolithic worshippers. Alas, it was easier to imagine the dashing scientist engaged in Indiana Jones-type exploits.

Then we headed back to Şanliurfa, where we’d started out. ARIT tours often involved visits to provincial archaeology museums, and we now paid our respects at the small Sanliurfa Archeology and Mosaic Museum, standing politely and listening to a stiff speech by the museum director before wandering through rooms of artifacts. After that we were given some free time.

Glad to be on our own, Sankar and I headed toward the El Ruha hotel, a lovely former palace and Old City landmark that we’d noticed on our previous visit. The complex comprised a series of golden tan stone buildings with flat rooftops and arched windows, portions of upper stories cantilevering out above the ones below. We noticed Alison sitting on an outdoor terrace with a cup of coffee, and joined her.

Allison had come to Istanbul in the 1980s to teach, and now worked as a dean at the Üsküdar School for Girls. Sankar and I were happy to sit down with her; we loved talking to experienced expats and sharing our own impressions. Now we quickly found ourselves talking about Turkish pride, a topic that had been bothering us. The issue was that in social situations with Turks, Sankar and I often hung our heads over our own country’s mistakes, but never witnessed any corresponding Turkish humility. Instead we always felt compelled to issue streams of compliments about the Republic. It was as if we needed to provide loyal reassurances as evidence of our friendship.

“Why can’t Turks be more balanced about their history?” I asked Allison. “Why can’t they talk about good and bad things in their past?” The Turks we knew considered themselves liberal and detested the Ottoman period, but refused to acknowledge what had happened to the Armenians under those same Ottomans.

Alison had a quick answer. “It’s too young a republic,” she told us. “It’s just too young. Give them a hundred years and it’ll be different.”

True: the Turkish Republic was only seventy five years old, less than a third of my republic’s lifespan. Ataturk’s struggle against four nations out to divide Turkey was still in living memory. It was a good answer.

Leaving Alison, Sankar and I walked through the dusty streets to the same covered bazaar we had visited with Gökhan and Burcu a year before. The market was maze-like, its only illumination seeming to come from the brightly colored and often sequined fabrics for sale. After a number of twists and turns, we reached a brighter central courtyard and sat down among locals, mostly men. Most were wearing Arab-style head coverings and traditional baggy pants rarely seen in Istanbul. Crowded and noisy, the atmosphere was evocative of the Arabian Nights, but we had been here before and knew that, even as odd-looking tourists—or perhaps because we were odd-looking tourists—we were safe.

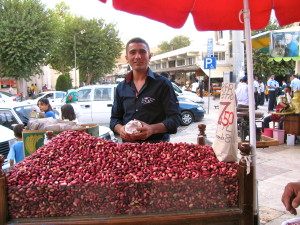

Saying no to several waiters offering tea, after a few minutes we got up and headed back toward El Ruha. The sidewalks were choked with street vendors, and one young man was standing at a wooden cart piled high with what looked like small pink almonds. His sign read “Fistik,” and we realized we were looking at freshly-picked pistachios, the pink a rubbery membrane over hard shells. Here was the rose-colored harvest of those dry, spindly-looking trees. Entranced by their appearance we bought a bag.

We sat down with our purchase alongside Şanliurfa’s biggest attraction, the Sacred Pool of Abraham. Abraham is the most important Old Testament figure for Muslims, who revere his unwavering faith and the obedience that led him to agree to sacrifice his son to God. The commemorative pool, built in the 1500s and about twice the size of an Olympic swimming pool, is surrounded by graceful arched columns topped with decorative crenellations, and full of koi fish that are considered sacred.

On the bus, Çiğdem had told us the pool’s legend. It had started as a spring of water that arose to protect Abraham when King Nimrod threw him into a fire. The spring’s fishy denizens had held Abraham up, saving him from being burned.

Rows of men squatted beside the pool’s edge, their arms stretched over their knees. Local families strolled along the water’s edge munching on snacks in small paper bags. When someone tossed a sesame roll into the water, it writhed and boiled with hungry fish. The afternoon sun gilded the arches and shimmered off the water, a scene of golden peacefulness.

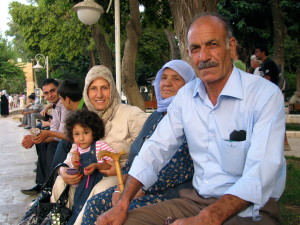

A Turkish gentleman of perhaps fifty-five was sitting near us with his family, and he turned to us, stuck out his hand, and introduced himself in Turkish as Aram. He had a strong, handsome face, receding gray hair, and a thin moustache. He asked where we were from. Turks often thought Sankar might be Turkish, but my presence confused them.

With our reply, “America,” Aram smiled broadly and, after asking us whether we had any children and whether we liked Turkey, he exclaimed, “I want to invite you to my house to stay and have dinner!”

On his other side sat the female members of his family, an older woman, perhaps his mother or his wife’s mother; a younger woman—maybe his wife, though she looked twenty years younger; and a little girl who looked to be about five. Although they hadn’t been consulted (were they now thinking, oh my god, what will we feed these people?) they beamed at us.

Though Turks are indeed friendly, the invitation was reminiscent of the more extravagant hospitality I’d experienced in Yemen. I recalled being told that in Turkey hospitality increased as one moved east—into more religiously conservative territory. What would Aram’s house look like? What kind of dishes would we be served? But alas, we couldn’t linger; our bus was leaving within the hour.

After declining as politely as we could, we asked if we could take a picture of the family. Aram agreed, and his wife pulled out a cell phone to take ours as well. “Gel, gel,”—“come”—he called to his little daughter to get her to stand still, and we repeated, “gel, gel,” imprinting that important word in our minds. Then we said goodbye.

Back at the Sanliurfa airport, my thoughts lingered on the land called Mesopotamia. The sites we visited–Gobekli Tepe, Nemrut Dagi, the Abraham pool–had been majestic, but temporal; all could be dated to particular eras. What had instead seemed timeless was Mesopotamian patriarchy. Men had always called the shots in this part of the world. Men were responsible for the aching grandeur of Mesopotamia. But they were also responsible for its destruction.

SOURCES

- Human Interaction with the Environment from Ancient Times to Early Romantic: Nature and the Stereotype of the Oriental, paper delivered at the National Endowment for the Humanities Institute on the Indian Ocean, July, 2002, by Josephine McQuail of Tennessee Technological University.

- Collapse: Why Do Civilizations Fail? Annenberg Learner