The student population of Özyeğin University had doubled in size in 2010, the year before I started work. In 2011, it doubled again. And it was predicted to double once again in 2012.

Turks equated school size with importance. I wasn’t sure why, but exponential scholastic growth was considered a very good thing.

I was often reminded of the old riddle: is it better to receive $5 a day for a month, or to receive a penny the first day, two cents the next day, and so on, the amount doubling for thirty days? I’d figured out as a child that one cent quickly became enormous. Now I imagined the student population at ÖzU doubling over and over, eventually taking over the world. How big—and how prestigious—was our university going to get?

In the fall of 2011, most ÖzU departments decamped to a newly built, vastly larger campus in Çekmeköy, a largely undeveloped part of Asian Istanbul. The School of English Language Instruction (SELI) was, for now, staying put. Thank goodness. Getting to and from Çekmeköy would have added at least an hour to my intercontinental commute.

SELI classes quickly filled the space left by other departments. Every classroom on two floors was jammed with students both morning and afternoon, and the teaching staff ballooned to over fifty. I liked to get to work early simply to think, because otherwise I didn’t have this chance. I would buy a poğaca (a savory pastry) and a cup of strong tea at the canteen and walk both floors, my heels echoing in the empty hallways.

One way to cope with rapid growth was to exert control. In the fall of 2011, I prepared to teach Level Four, Advanced English, under a new supervisor, Ceren, who was known as highly organized. Each Monday morning we eight Level Four teachers met with Ceren to discuss the upcoming week. Afterwards, we emerged with lengthy to-do lists, from evaluating extra teaching materials to downloading Turnitin, plagiarism-detecting software, to arranging library visits for our classes.

“Make sure to get your students’ topics this week,” Ceren told us as the module began. She wanted our students, during the initial week of class, to choose topics for required presentations they would give at the end of the eight-week module. We had already agreed on a list of acceptable meta-topics (psychology, transportation, etc.) based on chapters in our textbook. Ceren now asked us to give this list to our students, allow them five or ten minutes to think, and then have each select a specific topic.

I wasn’t sure why we needed to accomplish this task during the first week, but I was eager to comply with my new boss. As I went around my new classroom, however, stopping in front of each student and waiting to write down his or her topic, the exercise felt forced. Many students were finding it difficult to think all the way to the end of the module. Some couldn’t come up with any ideas at all, but instead wanted me to tell them what to choose. It would have been more useful to spend this early time building rapport rather than exerting my authority.

Level Four students were a few months more mature, and significantly more advanced in English, as there was quite a jump from Level Three to Four. Because we were better able to communicate with each other, it looked like we would get along better.

I needed to establish class rules on the use of electronic devices. On the first day I asked students not to use their ÖzU -provided Netbooks unless a classroom activity required it, and not to take phone calls in class—even from their helicopter-ish parents, whom they found difficult to refuse. That request seemed acceptable, but after class, one girl approached me and, near tears, explained that her aunt was dying and that a call could come at any time. Taken aback, I gave her an exemption.

ÖzU students received a ten-minute break each hour. At that time, I generally headed back to my office to relax and perhaps drink a cup of tea. But I quickly learned not to dismiss my students early. On the few occasions I’d done so, other teachers had heard their voices in the hallway and complained, asking me to please wait until the exact break time to avoid disrupting their students. Thereafter, if our lesson finished early, we all remained in the classroom, our eyes fixed on the clock.

When I left the class for breaks, students often commandeered the room’s sound system, connecting one of their Netbooks to it and broadcasting their favorite songs. When I returned, the room would be full of Western pop music or perhaps a mournful arabesque ballad. This was probably a no-no, but it didn’t seem important enough to forbid. Was I being hip and friendly—or simply a weary pushover?

One day I walked in to the song, Airplanes, by B.O.B., with its catchy refrain, “I could really use a wish right now . . . wish right now.” Airplanes happened to have been written by two of Greg’s college friends and I quickly pulled up Facebook pages of the two songwriters. The students were duly impressed. Another day it was simply a generic Western pop song, but as it ended, handsome, diminutive Sercan walked up to me at the board and confided, “Teacher, that song was supposed to be for my girlfriend and me at our wedding. But I wasn’t nice to her and she broke up with me.” I was touched that he felt comfortable enough with me to share this personal anecdote.

I had criticized Gülcan, my early Turkish teacher, for not understanding my Turkish. Now I often had difficulty understanding my students’ English. And it was awkward to say, “Can you repeat that?” over and over, even though (unlike Gülcan) I wore a pleasant expression.

I decided that, after a student had repeated a word a couple of times with no success, I’d ask him or her to write it down. Or I’d write it on the board and check to see if I had it right.

During the second week of the term, we started a unit on Architecture. I began by showing students slides of a number of diverse buildings, the concept being that architecture can create emotions in the observer.

“How do you feel when you look at this building?” I asked, displaying a photo of a concrete skyscraper.

“Rainforest,” answered a girl who didn’t usually speak up.

“Rainforest?” I asked, not sure I’d understood her. “You think of a rainforest when you look at this building?”

“Yes.”

Surprised, I nevertheless wrote the word on the board along with others students were giving me. A few minutes later the girl raised her hand again.

“No, teacher, I didn’t mean ‘rainforest.’ I meant rainforct.”

“Hmmm?” I replied.

“Rayinforced,” she repeated. And again, slower, “re-in-forced.”

On another occasion, the large number of expatriates in Istanbul came up, and several students suddenly wanted hear my answer to their question, “Is your husband show?”

“What?”

“Is your husband show?”

“Huh?”

Impatient, one of them went up and wrote it down on the board: “CEO.” Ah, they were trying to gauge how important Sankar—and I—were. “No,” I replied, “he is not a See Eee Ohh.”

“I’ve just finished writing the midterm exam, and I want you to give me your comments,” Ceren announced at our weekly meeting. She proceeded to hand out copies of the twelve-page Level Four exam we would give our students. Ceren’s English was excellent, and her draft looked good. Nevertheless several questions needed work. One simply needed a grammar fix, but two others were not written clearly. When everyone was finished reading, I brought these issues up, careful to first compliment Ceren.

It was only after the words were out of my mouth that I realized none of the other teachers, Turks all, were offering any suggestions. They were sitting silently, their faces impassive. And although Ceren was nodding at me, her face was stony. Well, there was nothing to do; I could hardly withdraw what I’d just said. We discussed the questions as a group, resolved them, and the meeting ended.

As I walked away, I chided myself for having irritated my boss. Why had I taken her request literally? Why hadn’t I waited to see what others did before I jumped in? It seemed I had failed to properly respect authority, and that superseded the accuracy of the exam itself. Well, one way to learn unspoken rules is to break them.

I wondered how we expatriate teachers, hired for our pronunciation and comprehensive English, were viewed by our supervisors. Most of us were only temporarily in Turkey, so we posed little threat to the hierarchy. But our tendency to think independently made us unpredictable. It was a case of Turkish control versus American independence, and I now began to notice that Big Nergis and her supervisors often ended directives with pointed looks in the direction of our foreign faces.

Due to the sheer volume of work, however, none of my supervisors ever had the time to come into my classroom to observe. And occasionally, Turks themselves broke rules. SELI was on a different schedule than the rest of the university, which didn’t allow for the short breaks between modules we teachers needed. So, every time a module ended, Big Nergis would, without permission from her higher-ups, grant us days off. I was delighted with this glimpse of Turkish disobedience; the hierarchy wasn’t seamless after all. But Nergis had to be careful, and the upshot for us teachers was that she granted these vacation days at the last minute, making planning nearly impossible.

During the third week of classes, we teachers put together the listening section of the midterm exam. This involved recording passages taken from written material—interviews or lectures. Native speakers were usually asked to make the recordings, and prior to one exam, I recorded a ten-minute “Interview with a Tennis Champion” in which I played the interviewer and Jane, a British colleague, played the tennis star. The students would listen to these recordings on exam day and answer questions about them.

“How did you progress to the top of your field?”

“Well, I showed lots of effort and perseverance. I was diligent in my practice habits. . .”

“Do you have any advice for others who want to succeed?”

In an incident that became notorious among us expatriate teachers, Charlotte, a newly hired teacher close to my age, was recording a lecture on architecture with her young Turkish supervisor, Tulin. As Charlotte read the script, she came upon a word that didn’t make sense. The passage was about how architects use lighting as a design element, but the word “lightning” was written on the page instead of “lighting.”

Charlotte corrected the error as she read, but Tulin stopped her. “Why did you say that? Why didn’t you say ‘lightning?’”

“Because it’s wrong,” Charlotte explained. “They mean ‘lighting.’”

Tulin spoke good English, so it puzzled me to hear that she hadn’t also caught the mistake. Perhaps her slip-up embarrassed her. “I want you to read the passage just as it is written,” Tulin directed.

I would have fought back instinctively and with little thought of consequences. If Tulin had continued to disagree, I would have insisted we march straight into Big Nergis’ office with the issue. Only later might I have regretted damaging my relationship with my supervisor.

But Charlotte didn’t do this. She simply reread the passage as Tulin wished.

With student issues taking up the majority of my time, these administrative conflicts were actually few and far between, Most days, I had nothing but admiration for the department’s precise organization, finding SELI a comforting, predictable place to work. But I sometimes wondered if it wasn’t just a little too sure of itself, too blind to other ways and possibilities. Might our students respond better if they saw their teachers as authentic thinking, searching human beings, rather than all-knowing enforcers?

In late fall, 2011, ÖzU admitted five Somalis, part of a larger group of international refugees the country had recently accepted. I had one of them, Abdi, a serious, attentive young man of about 23, in my class. On the first day of the module, Abdi asked me if he could come five minutes late to class on Fridays, the Islamic day of prayer. He and several other Somalis wanted to catch a bus to a nearby mosque.

I had never been asked that question by a Turkish student, not even the few covered female students I’d had who were presumably religiously conservative.

“Of course,” I replied. I wouldn’t think of getting in the way of his—or anyone’s—religious observance.

SELI was strict about attendance, however: we teachers took it at the beginning of every class hour. Allowing a student to regularly arrive late seemed like something I should mention to Ceren. When I did, she rolled her eyes, “It will be more than five minutes.”

“Don’t let him take advantage of this,” another Turkish colleague warned. “He’ll probably come later and later to class, and then other students will start showing up late, too.” How strange: here I was, a Christian in the middle of a Muslim dispute about mosque attendance.

I didn’t go back on my word to Abdi, but his compatriots in other classrooms, with whom he would have attended prayers, failed to get permission. And perhaps Abdi learned something about the Turkish culture: he ended up dropping the idea.

These situations provided rich dinnertime conversation material for Sankar and me, and it was gratifying that, both expatriates working in Asia Minor, we could now compare notes as equals.

Sankar had told me early on that Turks respected bosses with an authoritarian style, and strived to project an image of strength.

“They certainly seem to have trouble admitting mistakes,” I commented.

“Yes. I find them less humble than people I work with in India or China,” he mused. “They think they know stuff beyond what they really know.”

I thought of all of Turkey’s misspelled and mis-worded tourist signs.

“Part of it is that they’re afraid of harsh consequences from their bosses,” he added.

Hmm. Last summer, another supervisor had chewed me out in front of my office mates for not videotaping my students’ presentations, something I was supposed to do. I had noticed that nobody ever watched those tapes, and I didn’t want my students to see me fumbling with the equipment. And I recalled Umit proclaiming early on, “No more Turkish bosses.”

“They have a need to project pride and confidence. So they’re not self-critical,” Sankar continued. “And they really dislike being challenged in public.”

Ah yes. Ceren’s exam and my well-meaning comments.

“I’ve found that in private, Turks are much more flexible about taking criticism,” he went on.

“So I should have kept quiet at the meeting, but then maybe given Ceren a few suggestions when I had her alone?”

“Exactly.”

“Aren’t we kind of stereotyping Turks? They can’t all be alike.”

“Well, yes, but remember they’ve been brought up in a very standardized system here, whereas we foreigners come from all over the place.”

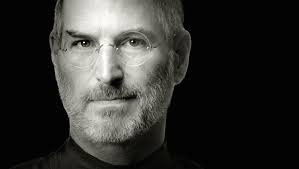

ÖzU was a business- and engineering-focused university, and in every hallway closed-circuit televisions hung, playing a continuous loop of science and business news. On October 5, 2011, those televisions informed us that Steve Jobs had died of cancer.

Although I’d known the Apple leader was ill, the news was unexpected. I felt sad—and also a little homesick. Whenever a major national event happened—I had been overseas during the Iran hostage crisis, the OJ Simpson trial, and the Oklahoma City bombings—I missed home. I longed for the NBC Night News, my local newspaper, and the chance to sit down with American friends for consolation.

But I had underestimated Jobs’ worldwide impact. Turkey is a highly connected country with a large percentage of computer-savvy young people. And even though Turks have a cultural reverence for control, Jobs’ unconventional creativity had captured their youthful imaginations. For over a week, business television ran retrospectives of his life. In class, my students asked me over and over again what I knew about Steve Jobs, and on Facebook they shared and re-shared photos, including the Apple logo brilliantly altered into Jobs’ bespectacled profile. Their grief was so heartfelt it seemed to speak to a deep yearning.

Within two weeks, the shiny white biography, Jobs by Walter Isaacson, appeared on tables in Istanbul bookstores. I peeked inside one copy, expecting it to be in English, but it had already been translated into Turkish.

My students had chosen topics for their oral presentations weeks before, and Ceren had the master list. Now several students approached me and asked if they could change their topics. Why? They wanted to talk about Steve Jobs.

I considered their requests. It really didn’t make any difference to me what they talked about. The important thing was that they developed an English PowerPoint and spoke in English for five minutes. I loved that they felt comfortable enough with me to ask for a change. So I told them it was fine. I simply asked them to confer with each other to make sure they weren’t all covering exactly the same aspect of the man’s life.

This breach in rules quickly produced another request. Suleyman, dreamy, fair-haired, and artistic, approached me and asked if he could also change his topic. He wanted to talk about Stan Lee, the nonagenarian American comic book writer and publisher. I hadn’t heard the name Stan Lee since my brothers collected Superman and Spiderman comics as young boys, and was amazed the man was still alive. I agreed, pleased my students would be working on topics they enjoyed. I hoped Ceren wouldn’t find out.

Students asking to change the rules. Teacher modeling American flexibility and independence. I was rocking to the Apple vibe: think different.