According to the Robert Frost poem, nothing gold can stay. Frost’s take on nature’s hues is poignant and the metaphor is broad. Brilliant, talented people have their day and then pass on. Grand and mighty cities fall into ruin. But there is a town in Europe that has “stayed” for nearly twenty centuries. And it has done so, in part, due to gold: brilliant, exquisitely detailed Byzantine mosaics.

A snug little city in northeastern Italy, Ravenna is not far from the Adriatic coast. In the age of Christ, Ravenna was, like Venice, a town built on pilings within a marsh. Julius Caesar massed his army there before setting out to cross the Rubicon.

CAPITAL OF THE WESTERN ROMAN EMPIRE

In 402 Roman Emperor Honorius proclaimed Ravenna, with its easy access to the sea, the capital of the Western Empire. In order to grow and better defend itself, the dominant branch of the Empire had moved east to Constantinople, now Istanbul. Honorius constructed civil and religious buildings in Ravenna, adorning the latter with mosaics. Honorius’ sister, Galla Placida, later took power there, defending Christianity from invading barbarians, and commissioning her own mosaic-laden mausoleum.

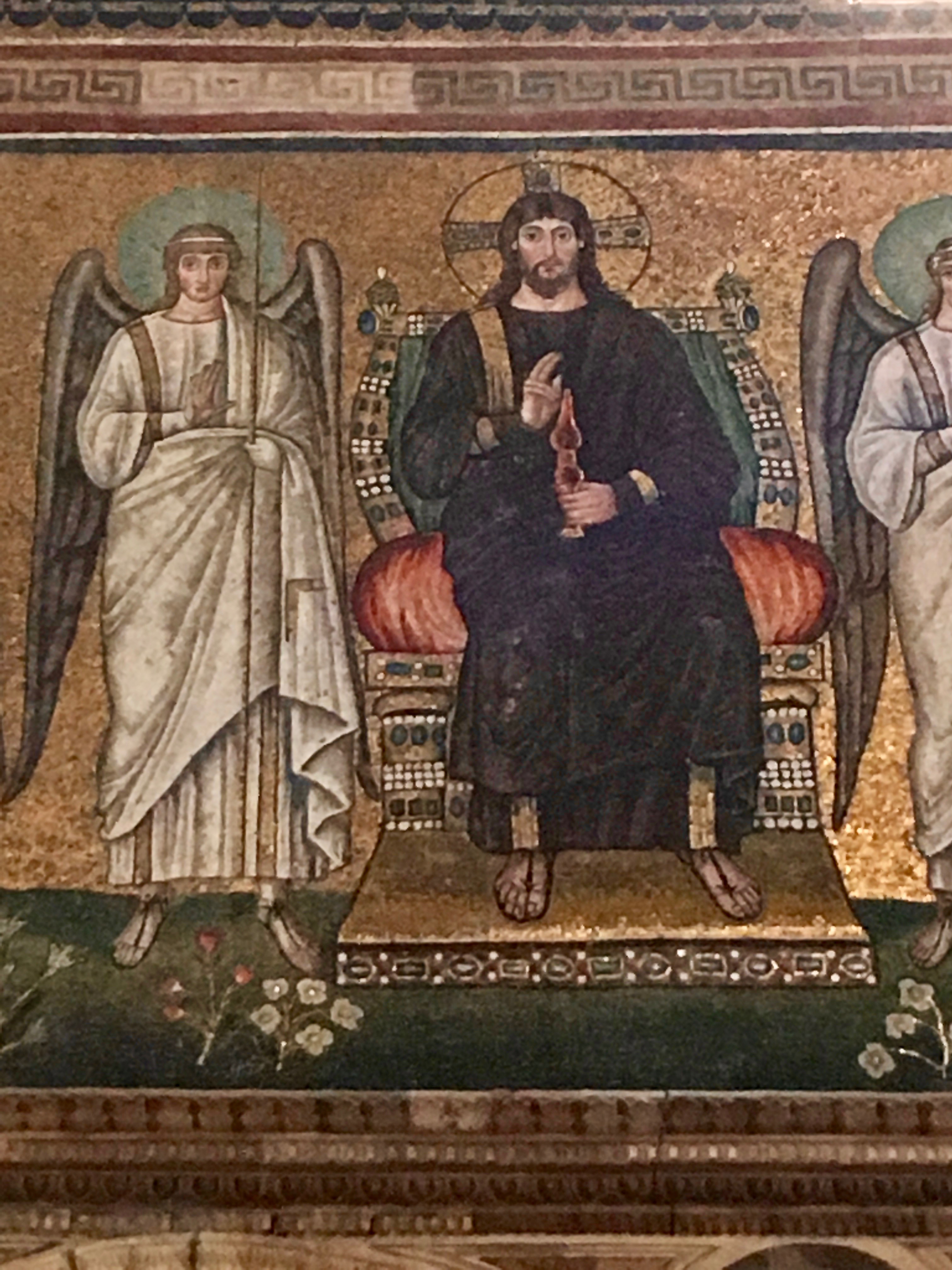

Mosaics are small pieces of stone and colored glass used to create artistic designs and representations. Byzantine mosaics were often gold in color, created by placing gold leaf under glass. Glass mosaics are the most brilliantly reflective of mosaics.

BYZANTINE MOSAICS IN THE GOTHIC AGE

In 476, Roman Emperor Romulus Augustulus was deposed by a non-Roman, Odoacer, who was then succeeded in 493 by Theodoric the Great. Odoacer and Theodoric belonged to the Sovereign of Ostrogoths. “The Goths,” from which the word, gothic derives, referring to things German or Teutonic, and architecture not classically Greek or Roman.

The Goths ruled Italy from Ravenna. Theodoric promoted the Arian version of Christianity, in which Christ is believed to be separate and subordinate to God, but he cohabited peacefully with Catholics. He also maintained the mosaic tradition; I imagine Roman mosaic artisans, timidly approaching the new ruler, hoping to stay employed. Theodoric restored Emperor Trajan’s imperial Roman aqueduct, and built the following:

BYZANTINE MOSAICS IN THE AGE OF JUSTINIAN

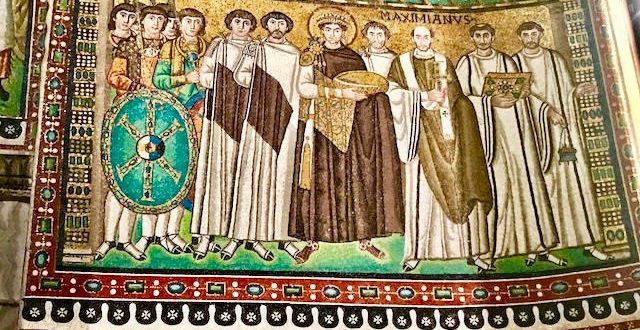

In 539, the Byzantine (basically, Rome in the East) Emperor Justinian overthrew the Goths. Based in Constantinople, he designated Ravenna as capital of the Prefecture of Italy. Justinian decorated Ravenna as lavishly he did Constantinople, with temples of marble adorned with fabulous Byzantine mosaic panels. These panels bring to detail scenes of Christ’s life as well as Byzantine court life. Two splendid basilicas: St. Vitale and St. Apollonare in nearby Classe, were built during this period.

THE END OF BYZANTIUM

Byzantium could not hold. Impoverished by battles with Persians and the followers of newborn Islam, the empire overextended itself. Its farthest flung parts spun off first: in the 8th century an Italian tribe, the Lombards, took over Ravenna. In 1453 Byzantine rule in Constantinople ended.

In its heyday Ravenna was subordinate to grand and glorious Constantinople. But Istanbul’s Byzantine mosaics were later plastered over, and not all have been restored. The mosaics of Ravenna remained gloriously intact. You can see them there today in basilicas, mausoleums, baptisteries, and chapels. The little subsidiary that stayed — it now outshines the main office.

For more on Byzantine mosaics, go to:

What a articulate post, and stunning photos of the best mosaics in the world! Ravenna is now high on my bucket list!