This is an excerpt from my upcoming memoir . . .

We were tired of spending every weekend in our apartment or close by, and we longed to establish some kind of connection with our new country. In early August, 2010, we decided to take a day trip to Iznik, formerly Nicea.

Iznik was the town I’d read about in Eyewitness Guide Turkey back in Minnesota. The guide had mentioned a Christian council held there that had produced the Nicene Creed, the statement of doctrine I had recited over and over as a churchgoing child. The town was just a few hours south of Istanbul, and it looked like an easy candidate for a day’s drive.

If Sankar and I had viewed this trip as a reality show challenge (“Amazing Race contestants: find a series of clues in the rat-filled, labyrinthine Karni Mata temple in India.” “Project Runway designers: create a couture gown out of materials found at a hardware store.”), we would have been more aware of its difficulties—and their inevitable effect on us. On paper, our challenge might have read: “Drive east out of Istanbul, following signs in Turkish to a scheduled ferry’s point of embarkation. After the ferry ride, locate a tiny, historic town and visit its most important museum. Then retrace your steps back to Istanbul.”

But we weren’t thinking “challenge.” We were thinking “fun trip outside the city.”

On the map, the route to Iznik was clear. We simply needed to drive east along the shore of the Sea of Marmara, and then, when we reached its edge, some 60 miles outside of Istanbul, peel away from the coastal superhighway for another 25 miles south.

But then the Turks weighed in. “Don’t go all the way by car. It’s out of the way. And there’s too much traffic,” Sankar’s colleagues told him. The map did show several highways converging at the east shore of Marmara, squeezed between the water and a set of foothills.

They suggested we take a ferry across Marmara, leaving from Pendik on the north side, and arriving at Yalova on the south side. It sounded interesting, but still, I thought, wouldn’t driving be simpler?

Sankar had his secretary, Didem, book ferry tickets for us and for our car. A boat ride in addition to a car trip. Well, it would probably be fun. As far as I knew, there were no car ferries in Minnesota.

This would not only be our first trip outside Istanbul, but our first real drive on our own. Because Umit always drove us (usually separately), the only places we had driven together were to the nearby Macro store for groceries, and twice to the Old City.

On Saturday morning we set off toward Pendik. We had noticed few people out on the roads on weekend mornings—perhaps Turks slept late—and today was no exception. In light traffic, we whizzed across the Second Bridge and continued east along the E-80 highway. The Turkish highway system is color-coded (green for superhighways and blue for lesser highways), numbered, and lettered, and highways often have several names. For example D-100 coming in from Bulgaria is blue, but becomes green E-84 near Istanbul. E-80, the major green highway through Istanbul, is also referred to as O-2 and O-4.

Umit, and then Sankar, had tried to explain the road system to me, but preoccupied as I was with Turkish vocabulary and simply finding my way around, I had triaged this information as too much, and discarded it. Temporarily, I thought.

The sun was shining as we flew past miles and miles of construction cranes; skyscrapers seemed to be going up everywhere. As Istanbul’s eastern sprawl thinned out, we began to look for a sign Sankar’s colleagues had told him about. It would be a picture of a boat and it, and companion signs, would lead us right to the point of embarkation.

Unfortunately, before we saw that sign, Sankar noticed an exit for “Pendik.” Afraid of making a mistake, he took it. We drove toward Pendik, but saw no boat icons. What had we done wrong? Now we began to worry, as the ferry was leaving in less than a half hour. We kept going straight and then saw a Öpet gas station. Sankar stopped and got out to ask directions. I am sure he used sign language and the word, nerede, where.

The proprietor, quickly surmising what two confused foreigners were doing in his provincial town, pointed the way to the boat. After just a few turns, we began to see signs with boat icons and astonishingly, the word, feribot, printed on them. Thank goodness Turks were organized—and a bigger thank you, Turks, for adopting a word from English! Before long we were turning toward the harbor and getting in line to drive onto the big, modern vessel.

Our inability to successfully navigate our gigantic new urban home weighed on both of us, but more heavily on me. Sankar was at least adept at performing his job duties. I often wandered around by myself, while he was ensconced in a now-familiar office, or being driven around another country by an English-speaking company employee (that had its own challenges, but usually didn’t involve getting lost). We were always operating under stress. Just the other day we’d been at Macro, trying to open multiple small plastic bags for our items on a tiny checkout counter while fumbling for our GarantiCard to pay for them. At some point we had set a bag on the floor beside us. Then, arms loaded we had left without it. We hadn’t missed the bag, containing wooden clothes hangars and cleaning supplies, until the next day. We knew we wouldn’t be able to explain to store personnel what had happened, so we resigned ourselves to their loss.

It was becoming clear to me that a large portion of my ego, a great deal of what made me proud as an adult, revolved around my ability to accomplish life’s tasks efficiently and effectively. In coming to Turkey without employment, I had fully anticipated a deflating loss of productivity, but surprisingly, more than anything else, I missed feeling confident in my own abilities. I missed setting out with a “to do” list and getting it all done on my own. I missed coming up with an idea—for example assembling the ingredients to bake a cake for Umit, whose birthday was coming up—and, on the spur of the moment, executing it.

I couldn’t remember feeling that loss so acutely during my other foreign assignments. Probably I’d been more humble in my twenties and thirties, less bothered about appearing the fool. I think something happens to us as we age; we believe more in ourselves, in our rightness. So perhaps I now had more to lose. And I’d always been conscious of how I appeared to others: a smiling confused young person is one thing. A smiling, confused 55-year-old is something else.

Lurking in the background was the realization that, even in my own country, my competence would be fleeting. In moments of pessimism, fortunately rare, I wondered whether my current bouts of forgetfulness were simply adjustment to a foreign country, or the beginning of some kind of mental decline.

The boat had three levels, two on top for seating and the lowest for cars and trucks. We parked the car, climbed to the second level, and sat down near the window on plush, upholstered seats.

I looked around at my fellow passengers, Turks of all ages: families, older couples, lots of children climbing over seat backs and walking hand in hand with adults. Lots of newspapers being read. Nearby, an extensive food counter presented itself: fresh cheese and salami sandwiches; various scone-looking rolls; an array of packaged almonds, pistachios and sunflower seeds; and tea bubbling in huge brass samovars.

It was only mid-morning, but my stomach was growling, so I got up and waited in line at the counter. When I reached the front, I pointed to a rectangular pan of flaky-looking pastry and asked, “Bu ne?” What is that? A silly question when the answer won’t be understood. Later I’d learn my eyes were good guides; this was börek, a savory breakfast pastry that would become one of my favorite Turkish dishes. I didn’t even know how to ask for it, so instead I pointed at a chocolate layer cake, asking for a slice. I also asked for two cups of tea (iki tane çay, literally two pieces of tea), which the clerk poured for me.

I gave her a pink and white ten Turkish lira bill and waited for my change. Several people came up to the counter at that point, however, and she began helping them. I stood waiting and feeling conspicuous, people lining up behind me, until finally I decided that perhaps I wasn’t going to get anything back. It was less than a dollar after all. I turned to leave, but as I did, the man standing directly behind me tapped my shoulder, motioning for me to wait, and then shouted at the clerk in Turkish, “You give her back her change!”

It was a perfect example of understanding language in context: the man’s words were as clear to me as if he had spoken them in English. I took the coins the clerk hurried to offer—she had simply been distracted, not trying to cheat me, I felt—and left feeling both conspicuous and comforted: I was being watched and watched over here in Turkey.

Sankar and I gazed out the window as we shared our cake. The Marmara was pale blue, its surface calm and misty. Big and little ships—oil tankers, container ships, smaller fishing vessels—were stopped at intervals, seeming to hang on the surface. They were, we later learned, waiting for clearance to pass through the Bosphorus.

Looking south, away from Istanbul, we couldn’t see any land at all: we were on a real sea, albeit one I hadn’t heard of six months before. Back in Istanbul, I looked up the Marmara’s surface area and doing some Midwestern comparisons, discovered that it is smaller than any of the Great Lakes, but nearly three times larger than Lake of the Woods.

In less than an hour we reached Yalova: modern, four and five story white buildings with red roofs, and a sunny, almost tropical ambience. As the boat approached the port, passengers left their seats to head down to the parking level, and we followed them. Unfolding our borrowed map, we reviewed the route and then slowly drove off the boat and turned south toward Lake Iznik.

On the map, Iznik Gölu looks like a tiny, oblong spawn of Marmara, but the real thing is impressively large. Later I learned it is about forty kilometers long and ten kilometers wide, about the size of Leech Lake in northern Minnesota. Its water was dark blue, and its surface ruffled by wind. Mountains rimmed its southern shore. We drove past olive groves in neat diagonal rows, their silvery leaves shimmering. Aside from olives, there was little development: none of the homes or summer cabins a big lake back home would attract.

After about a half hour, we begin to see the pastel-colored, boxy buildings of modern Iznik (population 15,000) ahead of us, curving around the eastern shore of the lake. Iznik would later become our touchpoint town, a miniature place we would come to know and navigate successfully. But now, concerned about not missing any turns, we failed to notice its fine scenery: the enchanting reeds and colorful fishing boats alongside the lake, and the steep, scenic ridges east of town.

I’d read that Iznik was founded in the fourth century BCE, and later fortified on three sides by a Roman wall. The Christian church had held seven councils across the centuries, all attempts to codify and standardize the new religion. The last of the Councils, in 787 AD, was held at Iznik’s Hagia Sofia church, not to be confused with the vast, world-famous Hagia Sofia in Istanbul. The name (Hagio, holy and Sophos, wisdom) means Church of Holy Wisdom, and was a common one for churches in Byzantine times.

We entered Iznik through an arched gate in the Roman wall. One side of the arch was supported with modern cement blocks, but the other side had small, rough reddish-brown bricks that looked original. A few blocks later we were in the center of town, and we parked and got out of the car.

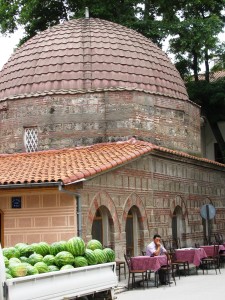

Mission accomplished, but now a new one: which of the old buildings in the streets surrounding us was the Hagia Sofia? We peered into a building on the main road that turned out to be an old mosque, and then a domed structure a few blocks south that was a Roman-turned-Turkish bath (later we would recognize baths simply by their domes, constructed so moisture could trickle down walls instead of dripping on bathers.)

A shop proprietor near the baths pointed us back toward the old church, a gray and reddish striped building on the main street. There were those earthquake-cushioning Byzantine stripes again.

The church building was squat and low, its brick and mortar surface rough with age. It had arched windows and a newly tiled red roof, and looked to be about one and a half stories high. There was no steeple, only several small cupolas poking through the roof like overturned fluted cups. On the south side stood a thick minaret about twice the height of the church. This was because it had been converted into a mosque after the Ottoman conquest, which had come to Nicea in 1331. The mosque had later fallen into disuse, and in the twentieth century the building had been turned into a museum.

The church seemed to have sunk, but this was likely due to centuries of sedimentation. To reach the door we walked down a half-flight of steps. We paid the seven Turkish Lira (about $4) entrance fee and entered. Inside was an elementary school gymnasium-sized room, with an earthy odor. The floor was covered with coarse gravel that had been swept away in several places to reveal faded Roman mosaic panels.

The young man who’d taken our money accompanied us around the building, enthusiastically pointing out features of the church. We nodded and I listened intently, willing myself to understand his Turkish. There were faded frescoes high up in a cupola near what we presumed had been the altar; stone risers in the spot where the council dignitaries had gathered (I understood his word, toplanta, meeting); and a niche along the south wall that looked like it had once held a grave.

On the north side of the building, we peered down through a protective glass pane over a window well. There in the dim light was a faded fresco believed to be from the 11th century. It featured the Deisis: Christ Pantocrator, the Virgin Mary, and John the Baptist. Jesus looked different from the image I’d grown up with. Painted in hues of gold, brown and blue, surprisingly rich after all the centuries, he had wild, dark hair and large expressive brown eyes. In his left hand was a gilded book. His right hand was extended upward, and on his face was a look of surprise.

It was one of those unexpected moments that draws together disparate emotions. Standing on the damp gravel, I thought back to the red hymnal I’d held open to The Nicene Creed as a child. I had never wondered about the creed’s history, but here I was in its faraway Muslim place of origin. I thought of our struggles to adapt to a complex foreign city, our longing for friends and family, and how in the last months I hadn’t even considered my faith.

So close to the land of his birth yet so far away in time, this expressive Jesus seemed to peer up at me through all the centuries. A constant in my otherwise upside down world. I found myself blinking back tears.

We emerged from the church in the noon light, and stopped for a moment, gathering ourselves. There were a few other things we wanted to see in Iznik. Insight Guides Turkey had portrayed vivid turquoise, red and royal blue patterned plates, vases, and urns, and stated that Iznik had, for several hundred years, been the center of Ottoman tile production. Just a few blocks east of the church, we saw a hand-lettered sign that read “Pottery Factories of 15th – 17th Century Ottoman Turkish Ceramics.” Behind a fence were several square brick structures, apparently centuries-old kilns being excavated.

Shops lining the streets sold modern replicas of these ceramics, and we bought some small framed tiles from a friendly, English-speaking artist. We completely missed the town’s fine ceramics museum, but would see it on subsequent visits.

Lunch was on the terrace of Kofteci Yusuf restaurant on the main street: a tasty platter of grilled meats and peppers, homemade flat bread and piquant salad.

Then, with over an hour until we needed to start back, we headed toward a small Roman amphitheater that was being excavated on the south side of town. No one else was around as we retraced its original curves, partially hidden by weeds, and crouched down to examine fragments of marble capitals, their carving still distinct after two millennia. Then we sat quietly for a few minutes, trying to conjure a performance.

After that we got in the car and drove toward a section of Iznik’s Roman walls, turning to follow them around the south side of town. Unfortunately, the road quickly deteriorated and we found ourselves in the middle of someone’s olive grove. Reversing, we nearly became mired in construction sand around the southern gate.

Finally, before heading back, we stopped and strolled along the park-like lakefront. No complexity here, simply a sparkling, limited expanse of water with a familiar, damp, fishy scent.

Reality program viewers know that, as time wears on, contestants become stressed and are increasingly likely to lash out at each other. The show gets more interesting. Sightseeing over, we still had the challenge of making the 3:30 ferry in Yalova and navigating back to Istanbul, admittedly not a difficult target to hit.

Getting to the ferry was no problem. Back through olive groves and into Yalova, passing a slew of feribot signs. A late afternoon boat ride, the sun slanting on the sea. Driving off the ferry, however, we were faced with an immediate choice: Green or blue road? Wishing to take the superhighway, Sankar headed in what he thought was the green direction, but the signs came too quickly and we ended up in downtown Pendik, surely blue territory.

The town had a strange feel that I would learn was typical of Turkish small towns. Apparently, land was at a premium, so the downtown area was built up with five- and six-storey buildings, residents packed into modern apartment blocks. For the better part of a mile, I got the feeling of being in an important metropolis, even as plowed fields peeked from behind the buildings.

As we drove through Pendik, we argued about how to get back onto the green road. I suggested what I thought was promising-looking turn, but Sankar did not react at all; he merely kept going. At once I felt anger rising, and then I snapped. “Why don’t you ever listen to me?”

“I am listening.”

“No. You didn’t even hear what I said.”

“I didn’t think it was the right turn.”

“Well then why didn’t you say so?” The car filled with acrimony.

What had happened? The day had been a success: we had accomplished what we’d intended to, and enjoyed the sights. But now our enjoyment, interwoven as it was with strss, was stripped away. And, after the initial rush of righteousness, I felt bereft. Sankar was the only person I knew on this side of the world, aside from employee Umit, and now we were furious with each other.

I remembered my parents bickering over directions on our family’s long-ago car trips. Pretty typical, but they weren’t alone in foreign territory. We couldn’t throw careless words at each other like we (and others) did back home because we had no one else to fall back on. Here our comfort and refuge had to be each other.

I had merely wanted someone to acknowledge my idea. But Sankar’s goal had been different. He had wanted, unrealistically, heroically, to avoid mistakes, to avoid getting lost and wasting time. He typically ignored that which he couldn’t quite trust, not realizing its effect on me. I realized I had brought something with me on the trip: an epic sense of grievance over my new feelings of unimportance.

Funny that in order to travel, in order to open up your world, you must first shrink it down. Down to just yourself or the one or two people you travel with. Down in size, to a tiny, combustible space.

We rode the rest of the way together in silence, the unwanted blue road nevertheless leading faithfully back to the city. Fortunately, one can only head west into Istanbul so far until one runs into the Bosphorus. Kind of like running into the truth.

We ended up near the First Bridge instead of the Second Bridge. Our poor sense of direction and marital discord would have cost us major points had we been competing against another team. But we did know how to cross the bridge and get home.